There’s a movement brewing between the lines of Twitter and within the deeper reaches of GitHub. Somebody is trying to “open source” contracts. You might have come across the term “open source” when downloading your favourite web browser. Open-source software is free, and it works. Is that what “open source” would mean for contracts?

I liked how Bonterms describes the motivation behind the endeavour:

Look inside the stack of nearly any major cloud application and you’ll find open source code, and lots of it. Developers leverage any existing package they can find before writing a line of code on their own. And they spend hours happily contributing back improvements to the projects they use. Open source has fundamentally transformed software development for the benefit of the entire ecosystem. But, could lawyers do the same? Could you possibly get law firm and in-house lawyers with the relevant domain experience to come together to articulate best practices, collaborate on drafting and then give their work product away for free? Yes, it turns out, you can. You just have to ask and provide a forum for working together and engaging in friendly, detailed debate.

Could time-starved lawyers used to charging by the hour be more like programmers and give what they do for free?

Standards, standards everywhere

Previously I wrote about an “open source” contract — OneNDA. There’s been good news on that front. They transformed themselves into Claustack and came out with oneDPA, backed by PwC and ContractPodAI.

Will oneNDA rule them all?oneNDA, a crowdsourced NDA, says it has standardised the NDA. Cue the sceptic in 3... 2... 1... Love.Law.Robots.Houfu

Love.Law.Robots.Houfu Back when OneNDA first came out, I hesitated to join the “hivemind”. My opinion has improved since.

Back when OneNDA first came out, I hesitated to join the “hivemind”. My opinion has improved since.

Other “open source” contracts have sprouted out recently — check out Bonterms and Common Paper.

It’s striking how similar these efforts are — all of them use some “cover page” mechanism to contract and are written by a “committee” of lawyers.

Here’s another similarity: all of them discourage modifying their templates.

You can see this from the particular license chosen by these projects. OneNDA chose CC-BY-ND 4.0 (the ND means no derivatives), and the others chose CC-BY (You might be able to make changes, even for commercial purposes, but you must credit the project when you make changes. How do you do that in a contract? 🤷🏻).

Even if you don’t know the difference between the various Creative Commons licenses, you’d be sufficiently discouraged by the documentation. One of the answers in the OneNDA FAQ is, “Yes, you can do whatever you like with it except actively allow or encourage people to change anything in oneNDA other than the variables.”

After I thought harder about the distinctions, I realised these projects aren’t so much about open source but standardisation. If everyone uses a particular contract, there will be massive benefits to all involved. However, you must agree to its restrictions — You can only modify the variables or the cover page. To use the contract, you must agree to all the choices and tradeoffs made by the project.

Philosophically, I disagree with this sort of standardisation. It’s apropos to introduce some XKCD:

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not going to sneer if I saw a OneNDA in the wild (I haven’t).

But I won’t overestimate the impact of these competing efforts at standardisation. On the one hand, nothing is stopping me from modifying any template. On the other, I don’t get any benefit from adhering to one too.

There is another aspect of “open source” that these projects might be alluding to. Open source development takes place in an open forum where anyone can contribute — on a mailing list, the GitHub issues page or some Discord server.

This idea that anyone can contribute appears to be anthemic to law. In the open source contracts I covered, all of them highlighted that they are supported or drafted by “experts” in their fields (I am a bit sceptical that someone would call themselves an NDA specialist). Both Common Paper and Bonterms have GitHub repositories for their contracts but don’t appear to accept contributions.

This brings me to Claustack. As mentioned above, it used to be OneNDA only, but now they have created a platform described as “GitHub meets StackOverflow – for lawyers”. The focus is not on the few documents that they are in charge of, but also on others including Bonterms and Common Paper. So, it is now a collection of resources, and a forum for people to provide feedback and suggestions, and at some level, be involved in its development. I liked this iteration better, so I joined up.

A contract standard might sound pointless because there are few, if any, restrictions to ensure you adhere to it. However, if there was a critical mass of users — a community — using, advocating and helping others on it, that is a recipe for conquering the world.

In “Forge your Future with Open Source”, a book about open source and how you can contribute to it, author VM Brassuer writes:

... the most important aspect of free and open source software isn’t the code; it’s the people. Contribution to [free and open source software] is about so much more than simply code, design, or documentation; it’s about participation and community. The licenses make the software available, but the people make the software, and the community supports the people. Remove one piece from this equation, and the entire system falls apart.

The quality of a contract might be important, and the licensing, the design and the cost of adoption are probably important too. But what would keep such a project going would be its people. At that point, more people have a stake in the success of the project, not just its founders or commercial backers.

Although I am cautiously optimistic about how Claustack is turning out, it’s still early days for these open source contracts. More has to be done in order to persuade other folks to contribute and advocate.

My lack of faith probably stems from my experience and observation that open source projects dealing directly with law and lawyers are very few and far in between.

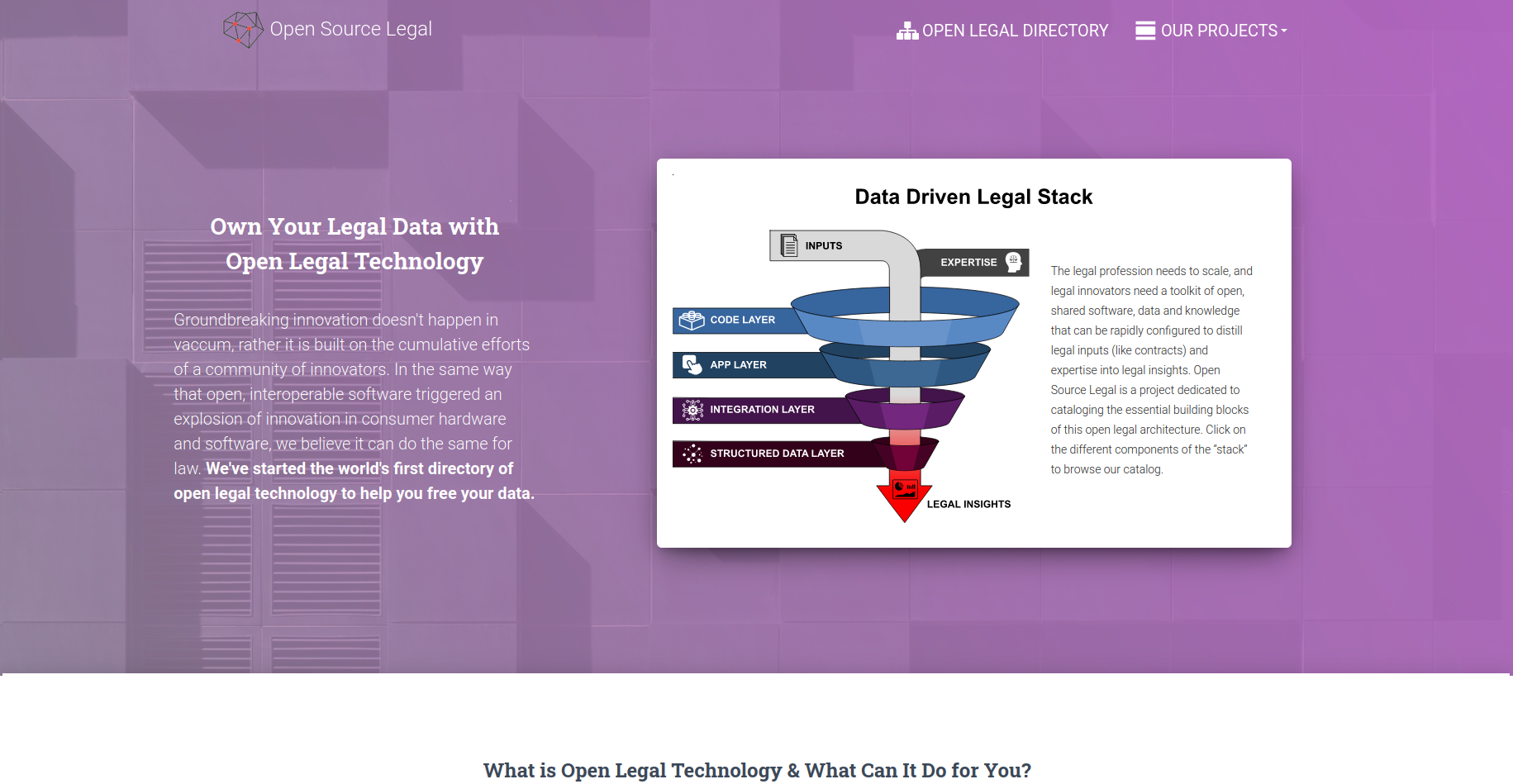

Open Source Legal: The Open Legal DirectoryOpen Source Legal is a central repository and review database of open and open source legal standards, applications, platforms and software libraries. It’s meant to help the legal engineering community track and develop a set of community-driven tools and standards to improve legal service delivery… Open Source Legal

Open Source Legal You can check out other open-source projects listed here.

You can check out other open-source projects listed here.

One such project which actually has a community is docassemble. They even have a yearly “DocaCon”. I attended my first last year (when the event was in person it was impossible for me to travel to Boston to attend it), and found a pretty weird tribe. Most of the excitement involved access to justice (A2J) implementations of docassemble, not something you would find in law firms or legal departments. I was excited at an effort to bring testing to docassemble interviews, again, I would never discuss this anywhere else.

In a recent interview on LawNext Podcast, Jonathan Pyle, benevolent dictator of docassemble, said this about his motivations for docassemble:

No, I really like to not make any money off of [docassemble]. It’s because I would really like being able to be honest to other people... I like being able to advise people not to use my code. It’s just so much easier if I could just concentrate on the technology and creating new features and not having to worry about making a living. It’s kind of nice to do something nice in the nights and weekends.

I can’t name another project like this.

Lack of opportunities is not the only problem. Culturally, lawyers seemed to be “trained” not to collaborate with each other.

Being #1 isn’t always a good thing—loneliness among lawyers (296) | Legal EvolutionSuccess as a lawyer can come at the expense of personal relationships. Is it worth the price? Few of my former partners in the global firm where I worked Legal EvolutionTom Sharbaugh

Legal EvolutionTom Sharbaugh In this detailed narrative, associates, partners and law students confront loneliness.

In this detailed narrative, associates, partners and law students confront loneliness.

Echoes of this also come from a recent interview with Mary O’Carroll on Artificial Lawyer.

If you have three lawyers in a room, and someone has information that can make someone else look good, will they help the other lawyers? Knowledge sharing between lawyers is not incentivised in training programmes. But, in a corporate setting you have to flex that muscle, i.e. collaboration and teamwork. The problem is that lawyers are trained to be the smartest person in the room. They don’t work cross-functionally in law firms. In a company however, every team has to work with every other team across the business.

Building a community for a normal open source project is really difficult. The question when it comes to open source contracts is: do lawyers even want a community?

Conclusion

An early draft of this post started by asking whether calling a contract “open source” is a PR stunt. It’s not fair to cast aspersions on an open source contract being given out for free when the usual course is not to share at all. Even so, one also has to be judicious about the way you spend your own time, something which lawyers are definitely (maybe overly) familiar with. Building an open source community is difficult, but that is what would make such a project sustainable. I’ll be keeping a lookout and hopefully there is a place for someone who wants to contribute.

#Contracts #docassemble #oneNDA #Claustack #Bonterms #CommonPaper #Law #Lawyers #Copyright

Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow this blog on the Fediverse [Enter the blog's address in Mastodon's search accounts function]

- Contact me:

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:

Image by

Image by  Photo by

Photo by  Image by

Image by  Photo by

Photo by  Image by

Image by

Artificial Lawyerartificiallawyer

Artificial Lawyerartificiallawyer