My review of Data Protection in Singapore in one graph

This post is part of a series on my Data Science journey with PDPC Decisions. Check it out for more posts on visualisations, natural languge processing, data extraction and processing!

It’s that time of the year! I wonderfully tackle trying to compress an entire year into a few paragraphs. If you are an ardent fan of data protection here, you will already have several events in mind. Here is just a few — the decision on the SingHealth data breach, the continuing spate of data breaches in Singapore, the new NRIC guidelines, or maybe the flurry of proposals from the PDPC ranging from AI to data portability.

You obviously can get all that from reading a newspaper. For this blog, I would like to dig a little deeper. This brings us to my ongoing data project analyzing data protection enforcement and practice in Singapore.

For now, I have been trying to reproduce what the DPEX survey does (but with automation and no interns). See the results for today’s post below:

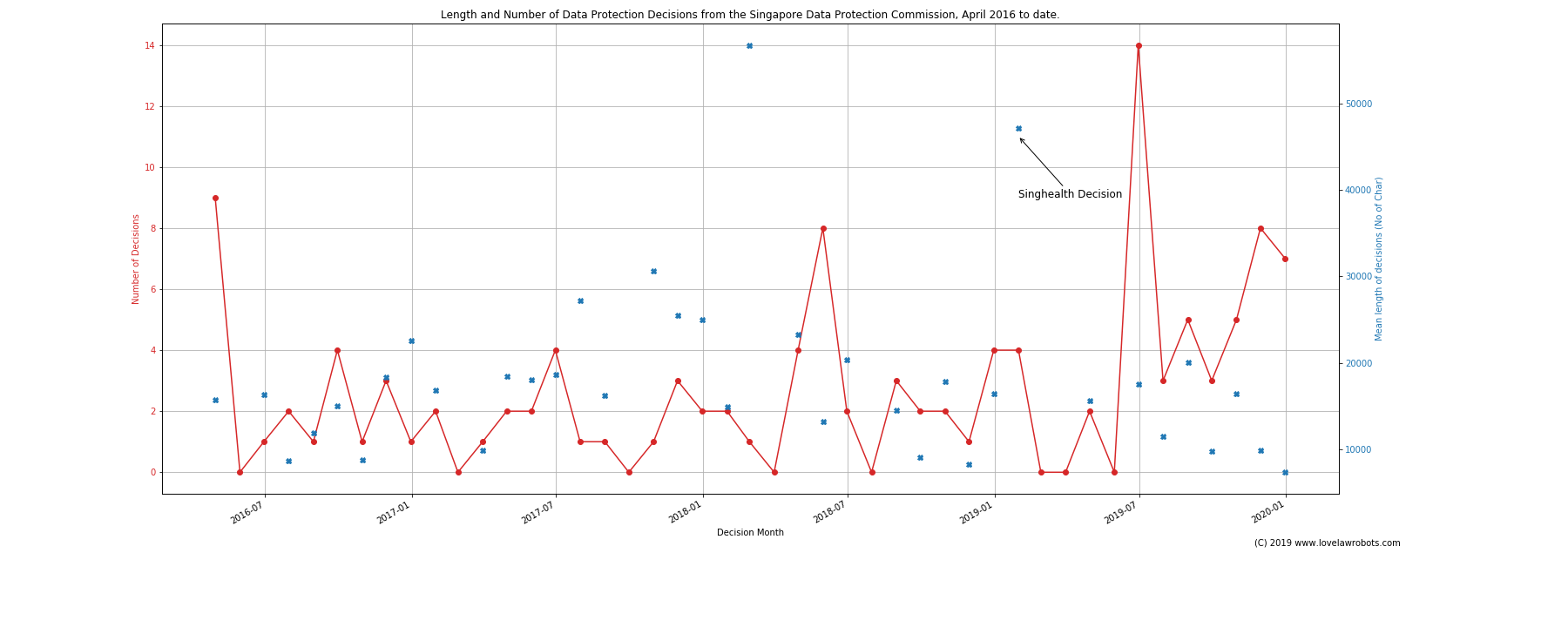

You are now looking at every decision that the PDPC has published to date.

You are now looking at every decision that the PDPC has published to date.

You can see from the decision marked as “Singhealth” that this is where 2019 starts. Here’s three observations I can draw from the data.

A. Singhealth was an outlier, the real change was in June 2019

You can see from the chart above that the average/mean length in January 2019 (the blue crosses) was nearly 50,000 characters. The Singhealth Decision was a very long decision, but it has proven to be an outlier. No decision since then has been afforded that level of detail.

Instead, one finds that in June 2019, there was a deluge of decisions, hitting a new high of 14 in that month (follow the red lines). Sudden peaks aren’t exactly rare. There are peaks in April 2016 (when the PDPC first released their decisions) and again in May 2018.

What did change since 2019 is that we find a regular monthly schedule of decisions Prior to this, the release schedule was punctuated with months without any decisions. Save for the aforementioned peaks, there was no month with more than 5 decisions. This appears to be the norm.

B. The decisions since June 2019 have been pretty short.

Coupled with the sudden deluge of decisions, the data shows that the decisions have been relatively short. That being said, they appear in line with the previous mean lengths per month. Follow the blue crosses, and you find that many of the numbers are well below 20,000 characters.

Statistically , this would appear not to be a big change. However, coupled with the number of decisions during that same period must be different. It’s easy to follow one decision a month. That’s different when you have to follow several a month.

I also noticed though this is not shown in the data, that the PDPC has more regularly used short case summaries these days. (See this example)

What do I think? The ground is shifting. A release schedule of 1 per month is great for studying particular decisions and jurisprudential concepts. A more regular schedule with several decisions is not conducive to studies but shows that enforcement has been a key focus.

C. More evidence of a shift in enforcement priorities by the PDPC?

In a previous post, I mused over whether the PDPC was now focusing on punishing companies which do not have data protection officers or policies. I even wondered whether there is a going rate of penalties for not appointing a DPO.

Now I wonder whether the PDPC feels that its role in educating the public about personal data concepts through its publication of decisions is done, and is now moving to publicise data breaches to educate the public on personal data enforcement. Simply put, no more Mr Nice PDPC anymore. It’s a side effect of the debacle caused by SingHealth and recent public sector breaches. You can cynically put it as trying to show the public that there are no angels in the private sector. My own belief is that more needs to be done to show the public that bad data practices are prevalent, and more work needs to be done. This is hardly a problem limited to Singapore, but it now feels real here.

For the record, I do not think that the PDPC’s role in publishing decisions to educate the public is done. Many grey areas still persist with regard to what “reasonable” means or what exactly the PDPC require organisations for third party diligence.

A new challenge for 2020

What do these budding trends mean? If the PDPC is indeed moving away from exploring the concepts of personal data through publishing decisions, and issuing short notes on enforcement instead, it becomes even more important to be able to suss out trends and analysis. Data Protection Officers have a lot of materials courtesy of the PDPC and the ever-expanding courses offered. However, the ability to analyze the messages coming out from enforcement, to prioritise which actions a DPO should focus on in order to protect their organizations, may be elusive.

I guess to some extent I provided a raison d’etre for my data project. By using automated means, hopefully, I can make this sustainable. What are you seeing out there? What kind of information would you be curious about? Feel free to let me know!

Check out the updated version of the graph:

#PDPC-Decisions #Singapore

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow this blog on the Fediverse [Enter the blog's address in Mastodon's search accounts function]

- Contact me: