Statistics take on the death penalty... and tumble

In one of my more popular posts last year, I remarked glibly that turning the outcome of 5 million random Monopoly JR games into a truth was magical. It wasn't funny because there was magic involved (there's none). It was funny because as a lawyer I couldn't wrap my head around it.

That's because this profession is very adverse to numbers and data. I don't know the reasons why, but you can witness the dismissive attitude towards it in a recent case heard at the US Supreme Court:

Roberts: Is there any evidence that 15 weeks is so much worse than viability?

Reproductive Rights lawyer: [data data data]

Roberts: “Putting the data aside…”— Elie Mystal (@ElieNYC) December 1, 2021

Or the uproar when the Supreme Court of Canada tried to describe its reasons in a diagram:

I stand by my concerns! ;)

— Amy Salyzyn (@AmySalyzyn) November 23, 2021

A disturbing statistic fails to convince

There's nothing funny about the death penalty in Singapore, though. A group of 17 Malays on death row for drug offences challenged their sentences. They don't allege that anything in particular happened to them. Instead, they point to statistics cobbled together from public sources showing that Malays were overrepresented in the death row — Malays made up 77% of Singaporeans on death row for drug offences, even though they only form 13.5% of the general population.

They thus alleged that the investigation and prosecution of drug offences discriminated against them, even if it was unconscious or not deliberate.

Unsurprisingly, the case was dismissed late last year. The judgement displays all the high watermarks of the scepticism the law has against statistics. Take this critical part of the judgement at [71] as an example:

Further, even if the plaintiffs’ statistical data is accepted as complete and accurate, the only variables reflected are the ethnic group and nationality of each offender. No account is taken of the multitude of other variables that would have contributed to the convictions and sentences in each case. The manner in which the plaintiffs’ statistics are presented therefore presupposes that all these offenders were equally situated and that the sole reason for differential treatment was their ethnicity, which are the very facts the plaintiffs bear the burden of showing.

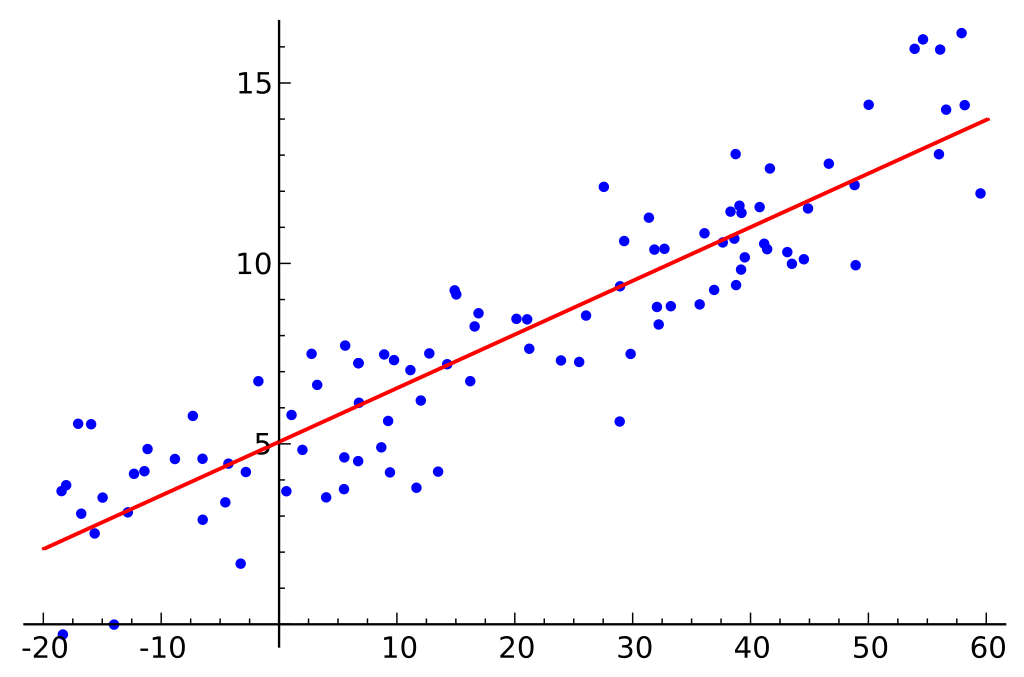

Any statistics presented as evidence will always have these problems because it is in the nature of statistics. Take a simple linear regression below as an example. The blue dots are samples and the red line is a linear regression, calculated by minimising the distances among all the samples. Only two variables are presented. The majority of the samples actually do not “fit” the line. This might be caused by some particular circumstance unique to the sample. “Common sense and logic” still tell us that there is a trend.

Source: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Linear_regression.svg

Source: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Linear_regression.svg

As such, the fact that not all accused are given death sentences or some get reduced sentences does not invalidate the trend that the cases are showing. If there was no discrimination, we would see a random distribution, not a trend.

The legal data does not tell us “why”

Even if we recognise that there is a trend, or in the context of the case that there is an overrepresentation of a particular community in sentencing, it doesn’t tell us why this is happening.

The problem starkly illustrates the conundrum that correlation does not imply causation.

Source: xkcd

Source: xkcd

We know how many people are given death sentences under the law, but there may be several reasons why there may be idiosyncrasies:

- Police are over-policing a particular community

- Prosecutors are less “lenient” towards a particular community

- Courts are inclined to give particular sentences

- A particular community is more “prone” to this type of criminal activity

- A particular community is less able to fight charges due to fewer resources (e.g. access to good legal advice)

A statistic alone would not be able to differentiate the cause or how much.

Without saying as much, the court appeared to have a lot of difficulty grappling with what exactly is causing the trend. At once, it isn’t sure whether the plaintiff’s case of discrimination is direct or indirect (see paragraph 62). Earlier in the judgement, we are treated to a scintillating report of double-crossing witnesses and a potential smoking gun, which was ultimately excluded (see paragraphs 5 to 15). In conclusion, the statistic by itself was not sufficient to prove or ground any case in discrimination under constitutional law.

The limits of legal data

The prosecution also went over a list of complaints that are commonly associated with statistical data (see paragraph 33):

- The makeup of the data does not explain itself — why from 2010? How is a particular offender considered as part of the Malay community or some other community based on the reported case alone?

- The data is selective and biased. No unreported cases. No cases from persons who avoided the death penalty in certain circumstances.

There are other potential problems. We don't know how significant this survey was,(the judgement does not say) but given that only 8 death sentences were passed in 2020, the number of cases considered is not likely to be significant. This means that cases affected by outliers such as random prosecution or offender decisions are likely to have a more significant impact on the sample and the result. This doesn’t mean that there was no discrimination — it means measuring it using statistics is difficult.

Ultimately, the number of people sentenced to death alone is probably not nuanced enough to tell us how fair or unfair a law is.

One should not take this too far though — the statistics prepared by the applicants might be based on the only information publicly available. Without easy access to complete and accurate data, it’s unfair to blame its imperfections on the applicants. However, this might also be the case where information isn’t even collected. How do we express the decisions of courts, prosecutors or the police in data and quantify bias in that?

Another point — while the data may not be perfect, proving something in law is not the same as in science. For example, in the criminal standard of proof, an accused is convicted when there is no reasonable doubt, and we accept circumstantial evidence even when we pass the death penalty for murder. I would believe that it is possible to form a winning case using statistics in combination with other evidence.

However, an advocate will need to be able to explain numbers and statistical concepts to a judge. This will not be an easy task in most contexts, and will only be reserved for the most confident of advocates.

Conclusion

This was one of many bad outings for statistics in the law. It might have been caused by a poor understanding of statistics or the limitations of using statistics in the legal sphere. I have yet to see a judgement demonstrate a sound grasp of these issues. If you do, please share!

#Singapore #SupremeCourtSingapore #DataScience #Judgements #Law

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow this blog on the Fediverse [Enter the blog's address in Mastodon's search accounts function]

- Contact me: