Three Things: Jigyasa

This one flew under the radar for some time. Jigyasa was first decided in March 2020 and then reconsidered almost a year later in 2021. (It was published in March 2021, and I am not sure whether the original decision was ever published in 2020 because neither I nor my robots noticed it). During that period of time, COVID happened. Ostensibly, that event allowed the penalty to be reduced from $90,000 to $30,000. Given the circumstances, it might be quite a reprieve for this respondent. Overall though, the decision brings troubling news for everyone else.

To summarise the details, the respondent is a sole proprietor providing Human Resource services. It is a small outfit dealing in “an extremely niched industry”. The personal data consisted of confidential 360 performance reports. As far as I am aware, 360 reports are generally prepared for upper, and middle management folks and consist of such good nuggets as “person should handle more complex responsibilities” and “slow support”. They were released in the wild through a misconfigured web application. The proprietor has no idea what these things do. As a result, these reports stayed on the Internet for 7 years.

Thing 1: The original penalty was harsh

As I mentioned, a $90,000 penalty is eye-catching. You don’t need a big data science chart to figure that out.Just play with the levers on the PDPC’s search, and you will find only three organisations that scored a $90,000 or higher penalty: Ninjavan, SingHealth and iHis. They aren’t sole proprietors.

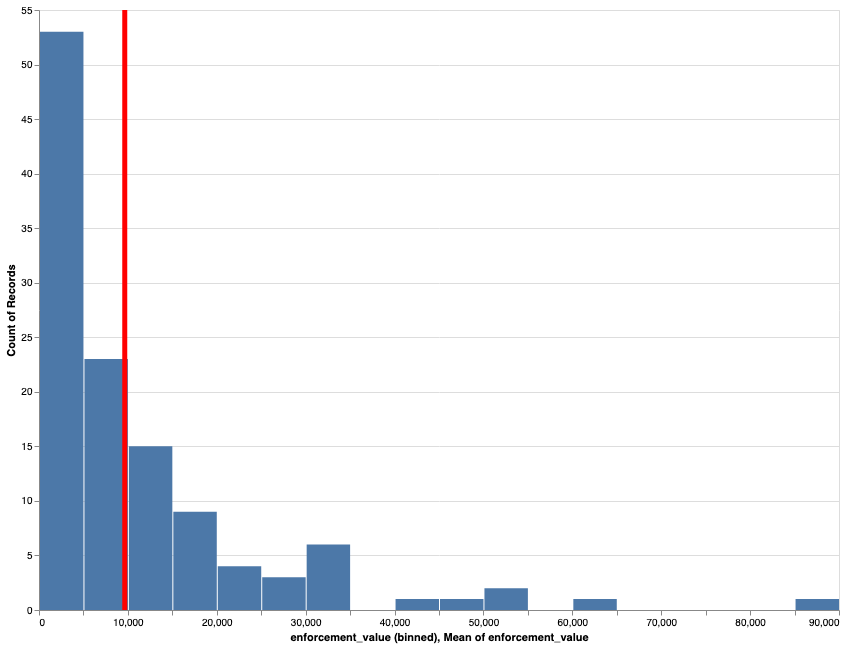

If you want a big data science chart though, I can share one from a project I did last year.

This is up to March 2020, so does not include the latest cases since then. Other notes in the original post still apply.

This is up to March 2020, so does not include the latest cases since then. Other notes in the original post still apply.

Ninjavan can be justified on the sheer scale of the breach (over 1 million persons affected). SingHealth and iHIS can be justified on the sheer scale (over 1 million persons affected, including the Prime Minister), as well as the medical data involved. To join this rarefied gang, we have Jigyasa, which left reports of 671 people online, causing (at least) one of the affected to fail his job interviews for over two years (allegedly).

Since we are doing this exercise, let’s move slightly lower than the $90,000 penalty. In Horizon Fast Ferry (2019), a company operating ferry services exposed the personal data (including passports) of nearly 300,000 passengers. They didn’t have a data protection policy or officer either. Frankly, they didn’t tell their contractor to do anything about data protection, so the overall impression was cluelessness as well. The penalty? $54,000.

Of course, there is no magic formula for determining the penalty, and each case considers “the specific facts of the case to ensure that the decision and direction(s) are fair and appropriate for that particular organisation”. However, these cases don’t exist in a vacuum, and fairness requires considering whether each respondent is treated fairly compared to the others.

Thing 2: Collecting personal data without consent is an aggravating factor?

If one compares the millions and thousands of people affected in other cases and the 671 in Jigayasa, which resulted in similar or lower penalties, then there must be something special about Jigyasa.

We now arrive at the decision’s most controversial premise. In arguing for a lower penalty, the respondent claimed that because the information was collected under an exception under the PDPA and disclosed without consent, the breach was less serious. This sounds intuitive the first time, but what has consent to do with the severity of the breach? This is a breach of a protection obligation, not an obligation to get consent.

The PDPC decided instead to give the argument a roundhouse kick and charge that a higher degree of protection was required because consent was not required. In fact, the PDPC argued that not having to get consent had a consequence:

The quid pro quo for organisations having the liberty to collect, use and disclose personal data without consent for evaluative purposes, and to keep opinion data beyond the reach of data subjects for access and correction, is that they are expected to put in place more robust measures to comply with the Protection Obligation.

I was stunned by the “ quid pro quo ” argument made by the PDPC and wanted to find out whether I missed something. The decision does not cite any support that the exclusion framework for evaluative purposes implies a quid pro quo approach.

The Parliamentary debates regarding the exceptions in the PDPA did not mention the evaluative purpose specifically. I did find this explanation regarding the exceptions in the PDPA:

Sir, Mr Desmond Lee asked about the exceptions provided in the Second to Fourth Schedules. These are based on the overarching intent of ensuring adequate protection for individuals without placing onerous burdens on organisations to comply with the law. They also take into account international practice and Singapore’s context. For example, exceptions apply in certain circumstances or situations where obtaining consent for the collection, use or disclosure of personal data may not be feasible. Such situations include collection of personal data for life-threatening emergencies. Exceptions are also necessary to enable certain organisations to effectively perform their functions, such as investigations or legal proceedings.

It’s not easy to square both passages together, but the message now appears to be that information collected under the evaluative exception should be treated as riskier than others.

Even though the PDPC claimed that this quid pro quo structure only applies to the evaluative purpose exception, it’s hard not to see how the argument can easily apply to any other exception. This includes the new exceptions, such as business improvement purposes. These new exceptions are not “necessary” to perform business functions and ultimately benefit the consumer in some way, so there can be a quid pro quo arrangement too. Given this decision, organisations must look into the data they are storing and pay special attention to data collected under an exception.

However, if you have been mindful of data protection in the first place, you would already know that whatever personal data you have should be protected, regardless of how they were collected.

Thing 3: Penalties can be arbitrary, avoid them if you can

I wasn’t expecting that relying on an exception to collect data would result in heavier penalties. The impression I had was that they were meant to reduce the compliance burden of companies.

There are several ways to rationalise the impact of this decision. The PDPC already said this reasoning is limited to evaluative purposes. Each case stands on its own. The PDPC continually reminds the public that each case and each penalty is due to its unique circumstances. I have not read a decision whereby the PDPC refers to a past decision as a basis for the calculation of the penalties. We can sweep this decision under the carpet as it did for a year hiding behind COVID-19.

I instead feel that the best response to a decision that I think is cruel, arbitrary or irrational is to think of ways out of it. Unlike criminal law, where the best action to avoid speeding tickets is by not speeding, the PDPC’s approach to active enforcement suggests more alternatives. These include voluntary undertakings (NEW in the amendments) or an expedited decision.

In a voluntary undertaking, the respondent has more control over the outcome of a case. We are talking about * remediation, not mitigating factors.* We are also talking about the respondent’s plans, not the PDPC’s directions.

Furthermore, I haven’t read any media outlet that attempts to explain a voluntary undertaking in the context of a data breach. You might not even know there is a new section on the PDPC’s website.

Unfortunately, to quickly develop a remediation plan that would satisfy the PDPC, you will need professionals specialized in the field. I believe that this is really the strongest case for hiring your own data professionals, especially in light of the new amendments to the PDPA.

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow this blog on the Fediverse [Enter the blog's address in Mastodon's search accounts function]

- Contact me: