Assumptions, reassessed

Like most people, I hate to be wrong. But if I got things right all the time, I’d be a judge, not a blog writer.

More than a year ago, I highlighted the only case on the Personal Data Protection Act I am aware of that has reached the High Court. It was a “rare sighting” of a private action under the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA).

In the post, I concluded that the right of private action was “meaningless” because the High Court held that you cannot claim “distress and loss of control”. That was, after all, what most people face when their privacy is breached. Even so, I thought that individuals going after companies for a breach was too much for one person to bear. That case, after all, concerned a rich, disgruntled data subject facing an intransigent data controller.

The case had gone on appeal to the Court of Appeal, which is understandable, given that the PDPA has never been before the highest court of the land, so clearly there are interesting and novel legal questions to be heard.

Furthermore, the Attorney General’s Chambers (AGC) also participated in the appeal. This is noteworthy because it intervened in essentially a private action. However, as mentioned above, the questions are novel, so the drafters of the PDPA should have a say.

The AGC's submissions largely echoed what I accepted in my previous post. This was essentially how we expected to read the legislation. This included accepting the general belief that emotional distress is not claimable under law.

Well, the Court of Appeal has spoken, and I was wrong.

The Court of Appeal held that “distress and loss of control” can be the subject of a right to private action. This was different from the common law, which generally does not regard emotional distress as actionable. (You can’t make a claim against another person for making you feel sad; such is “the vicissitudes of life”.)

What do I read from this? The Court probably abhors meaningless rights. As noted in my previous article, following the lines of the Government and the High Court’s judgement, the private action was not useful to anyone who had their privacy breached.

With the Court of Appeal’s pronouncement, the right to private action has more life in it. However, it’s still probably impracticable to exercise. Not only does a claimant have to bear the costs and stress of litigation, but it also depends on the actions of the respondent. In the instant case, the respondent explicitly (and inexplicably) refused to undertake not to use data without consent. The private action would be wholly unnecessary if everyone acted reasonably.

It was surprising to me that the Government’s position was not accepted by the Court of Appeal. The big picture is that there will always be some uncertainty about how the Court would read a piece of legislation in a dispute. This might make the Government’s recent insistence that only Parliament can decide what is marriage more understandable.

For now, until the Court of Appeal says so, maybe we shouldn’t be too confident when we make predictions on what the law is.

#Law #Singapore #SupremeCourtSingapore #AGC #ConsentObligation #Enforcement #Government #Judgements #Lawyers #Legislation #News #PersonalDataProtectionAct #Undertakings

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow this blog on the Fediverse [Enter the blog's address in Mastodon's search accounts function]

- Contact me:

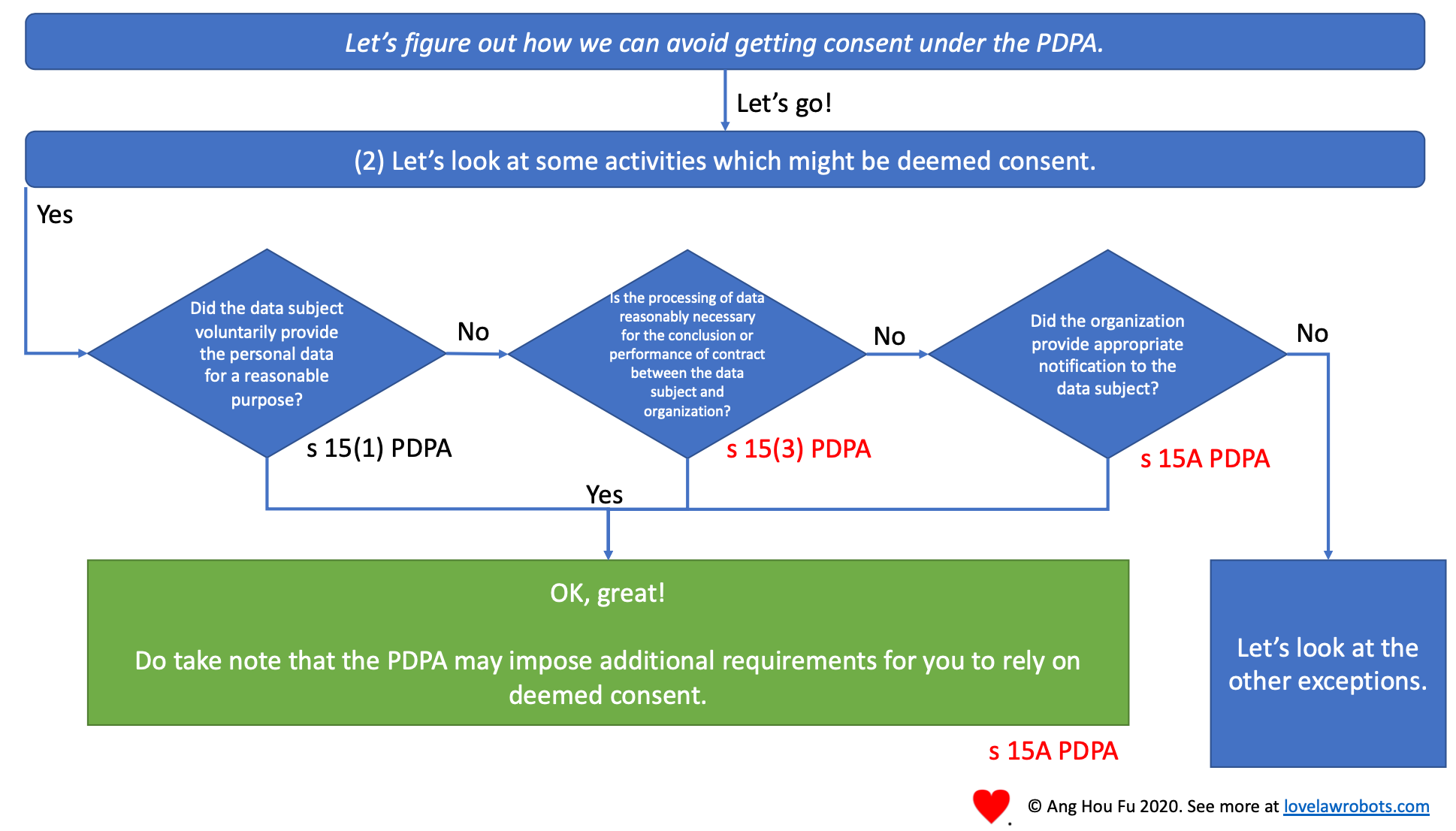

Deemed consent has expanded.

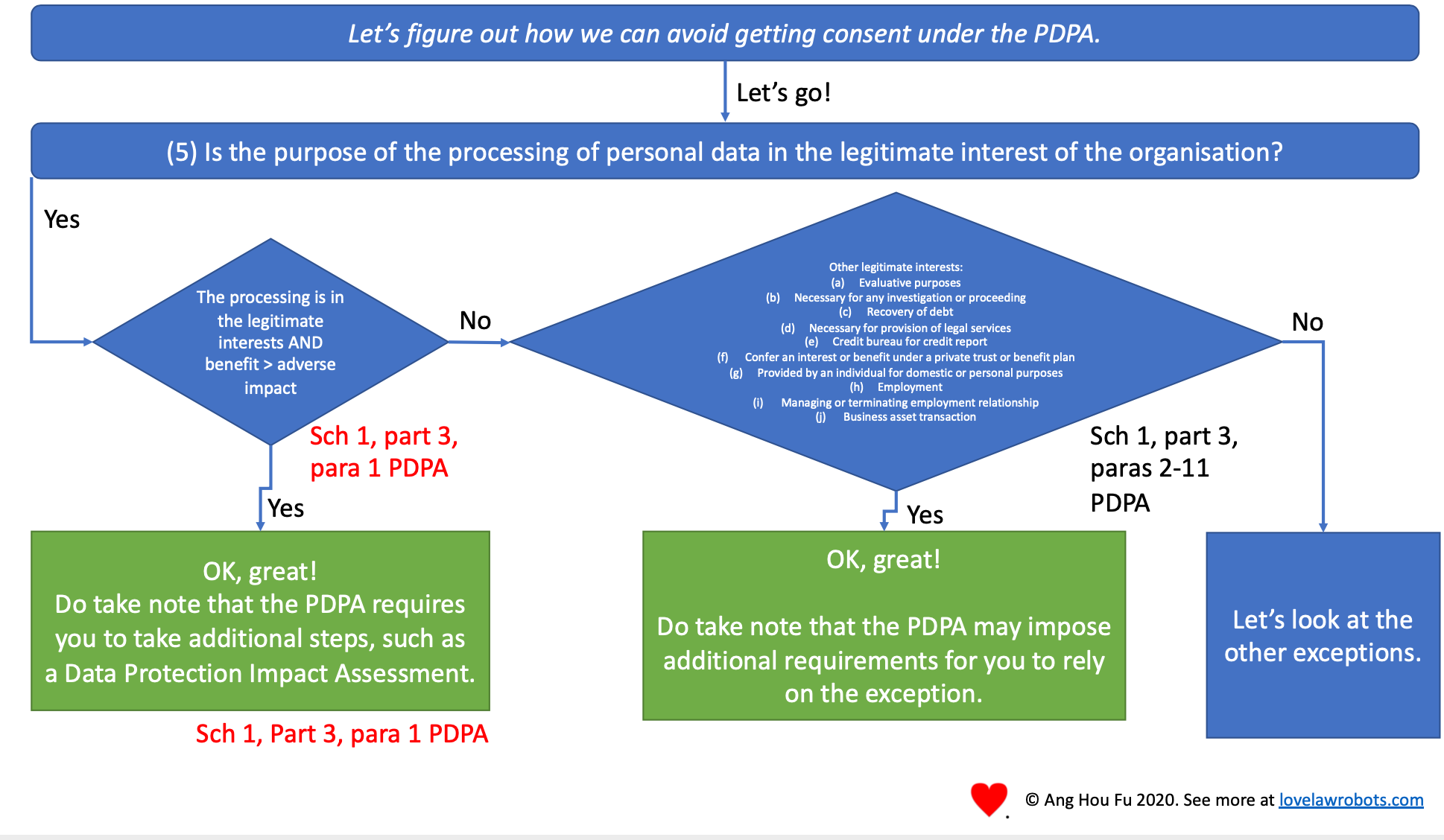

Deemed consent has expanded. A new legitimate interests exception.

A new legitimate interests exception.