Will Increased Penalties Lead to Greater Compliance With the PDPA?

This post is part of a series relating to the amendments to the Personal Data Protection Act in Singapore in 2020. Check out the main post for more articles!

When the GDPR made its star turn in 2018, the jaw-dropping penalties drew a lot of attention. Up to €20 million, or up to 4% of the annual worldwide turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is greater , was at stake. Several companies scrambled to get their houses in order. For the most part, the authorities have followed through. We are expecting more too. Is this the same with the Personal Data Protection Act in Singapore too?

Penalties will increase under the latest PDPA amendments.

The financial penalties under Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act probably garner the most attention. They are still newsworthy even though they have been issued regularly since 2016. The most famous data breach concerning SingHealth resulted in a total penalty of S$1 million. The maximum penalty of $1 million is not negligible. It’s not hypothetical either.

The newest PDPA amendments will now increase the maximum penalty to up to 10% of an organisation’s annual gross turnover in Singapore. To help imagine what this means: According to Singtel’s Annual Report in 2020, operating revenues for Singapore consumers was S$2.11b. The maximum penalty would be at least S$200m.

Is this the harbinger of doom and gloom for local companies? Will local companies scramble to hire personal data specialists like for the GDPR? Will an army of lawyers be groomed to fine-comb previous PDPC decisions to distinguish their clients' cases? Is my CIPP/A finally worth something?

Penalties imposed under the PDPA appear limited.

Before trying to spend on compliance, savvier companies would want to find out more about how the Personal Data Protection Commission enforces the PDPA. This makes sense. The costs of compliance have to be rational in light of the risks. If the dangers of being susceptible to a financial penalty are valued at $5,000, it makes no sense to hire a professional at $80,000 a year. If liability for data breaches is a unique and rare event, hiring a firm of lawyers to defend you in that event is better than hiring a professional every day to prevent it.

So here is the big question: What’s the risk of being penalised $1 million or gasp(!) at least $200 million?

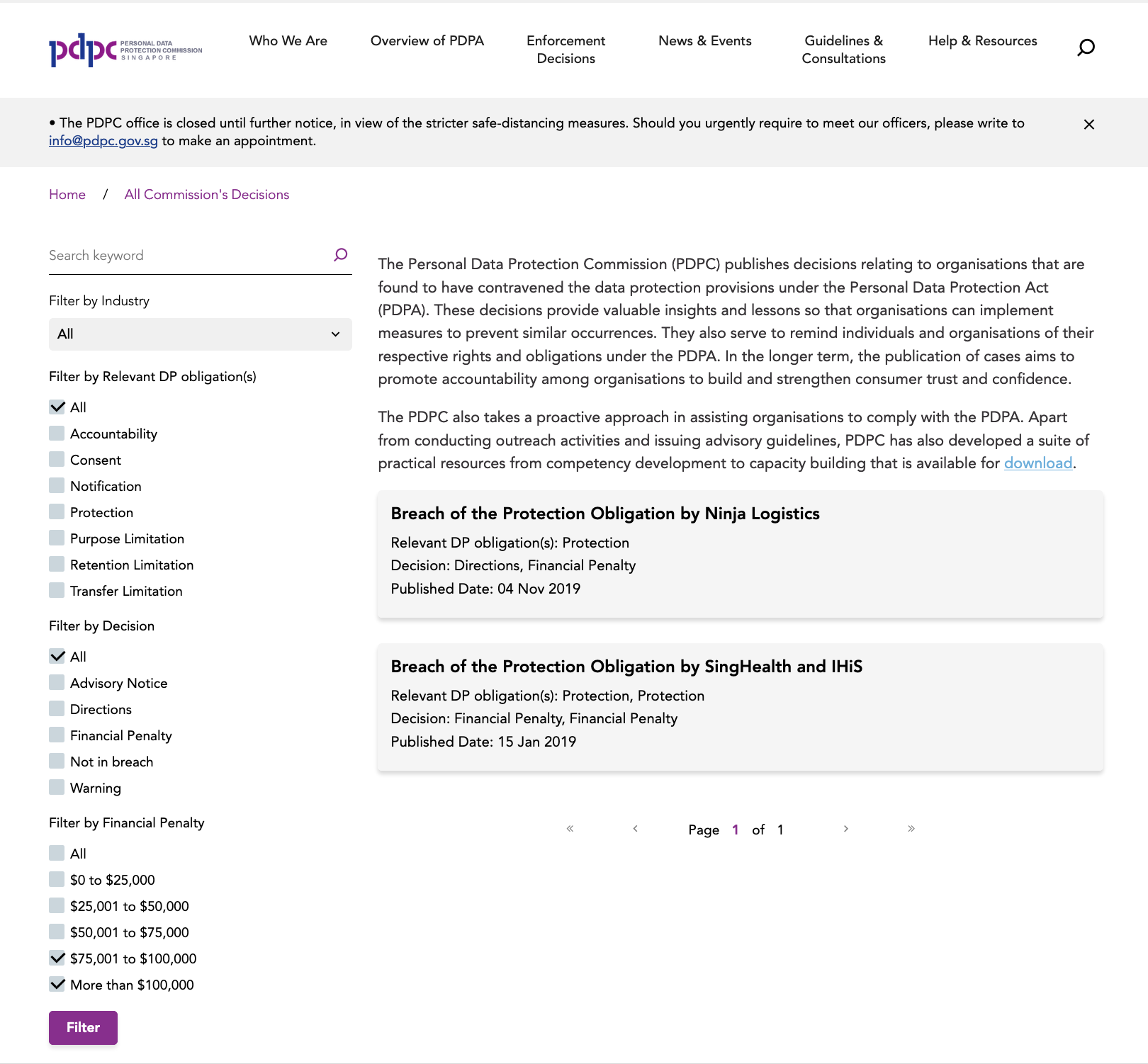

Unfortunately, one does not need a big data science chart to realise that being penalised $1 million is a rare event. Being penalised $100,000 is also a rare event. Using the filters from the PDPC’s decisions database reveals a total of 2 cases with financial penalties greater than $75,000 since 2016.

Screen capture of filters of PDPC decisions with financial penalties of more than $75000. (As of October 2020)

Screen capture of filters of PDPC decisions with financial penalties of more than $75000. (As of October 2020)

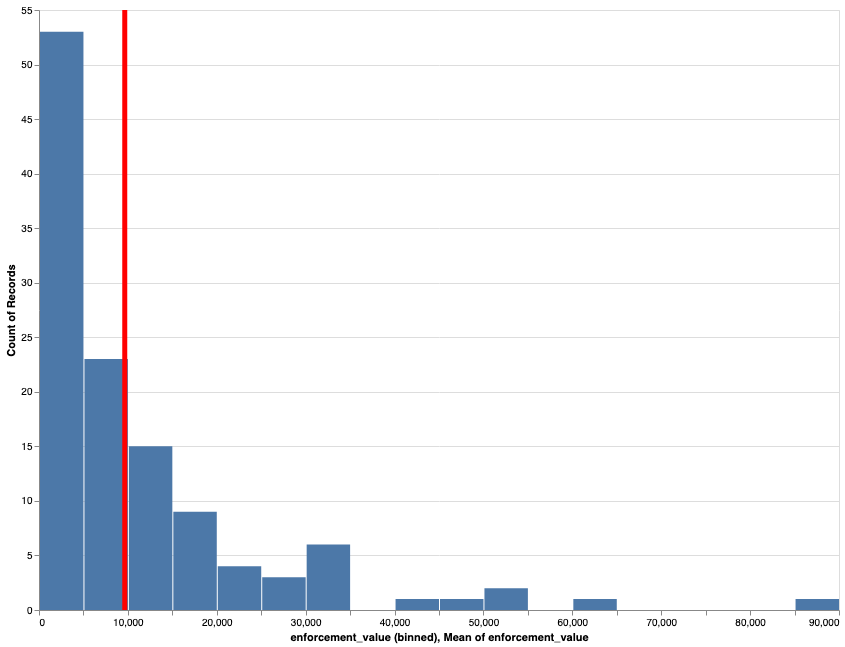

However, if you insist on having a “big data science chart”, here’s one I created anyway:

Histogram of the number of cases binned on enforcement value.

Histogram of the number of cases binned on enforcement value.

Notes :

- I excluded the Singhealth penalties ($750K and $250K) because they were outliers.

- It’s named “enforcement value” and not “penalty sum” because I considered warnings and directions to have $0 as a financial penalty.

The “big data science chart” tells the same story as the PDPC’s website. Most financial penalties fall within the $0 to $35,000 range, with the mean penalty being less than $10,000. While the PDPC certainly has the power to impose a $1 million penalty, it appears to flex around 1% of its capabilities most of the time.

Past performance does not represent future returns. However, the amendments to the PDPA were not supposed to represent a change to the PDPC’s practices. They are for “flexibility” and to match other areas like the Competition Act. There is very little indication that an increase in the financial cap now means that companies will be liable for more.

Why are the penalties so low?

The decisions cite several factors in determining the amount of penalty – the number of individuals affected, the significance of the data lost and even whether the respondent cooperated with the PDPC.

In Horizon Fast Ferry, the PDPC cited the “ICO Guidance on Monetary Penalties” as a principle in determining monetary penalties:

The Commissioner’s underlying objective in imposing a monetary penalty notice is to promote compliance with the DPA or with PECR. The penalty must be sufficiently meaningful to act both as a sanction and also as a deterrent to prevent non-compliance of similar seriousness in the future by the contravening person and by others.

The key phrase in the quote is “sufficiently meaningful”. Given the PDPC’s desire to promote businesses, the PDPC would not like to kill off a company by imposing a crippling penalty. The penalties serve a signalling purpose. As they continue to attract public attention and encourage companies to comply, penalties are the most effective tool in the PDPC’s arsenal.

However, even if the penalties are “sufficiently meaningful” in an objective sense, they may still be meaningless subjectively. $5,000 might be peanuts to a large business. Some businesses may even treat it as a cost of “innovation”. PDPC decisions are replete with “repeat” offenders. Breaking the PDPA, for example, seems to be a habit for Grab.

While doling out “meaningful” penalties strikes a balance between compliance with the law and business interests, there are limits to this approach. As mentioned above, dealing with a risk of $5,000 fines may not be sufficient for a company to hire a team of specialists or even a professional Data Protection Officer. If a company’s best strategy is not to get caught for a penalty, this does not promote compliance with the law at all.

Moving beyond penalties

I am not a fan of financial penalties. I have always viewed them as a “transaction”, so they never really comply with the spirit of compliance.

Asking companies to comply with directions may be far more punishing than doling out a fine. A law firm might help you negotiate the best directions you can get, but the company has to implement them through its employees. The company will need data protection specialists. This approach is more effective than just essentially issuing a company a ticket.

For this reason, I was pretty excited about the PDPC’s Active Enforcement guidelines. Here’s something to watch out for: a new section on undertakings appeared last month.

Conclusion

Still, I am probably an outlier in this regard. The increased penalty cap has repeatedly featured as one of the most critical changes in the PDPA. Experience does not suggest that a higher cap will change much. Nevertheless, as a signal, the news would probably make management sit up and review their data protection policies. Data Protection Officers should take advantage of the new attention to polish up their data protection policies and practices.

This post is part of a series on my Data Science journey with PDPC Decisions. Check it out for more posts on visualisations, natural languge processing, data extraction and processing!

#Privacy #Singapore ##PDPAAmendment2020 #Compliance #DataBreach #DataProtectionOfficer #Decisions #GDPR #Enforcement #Penalties #PersonalDataProtectionAct #PersonalDataProtectionCommission #Undertakings

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow this blog on the Fediverse [Enter the blog's address in Mastodon's search accounts function]

- Contact me:

Deemed consent has expanded.

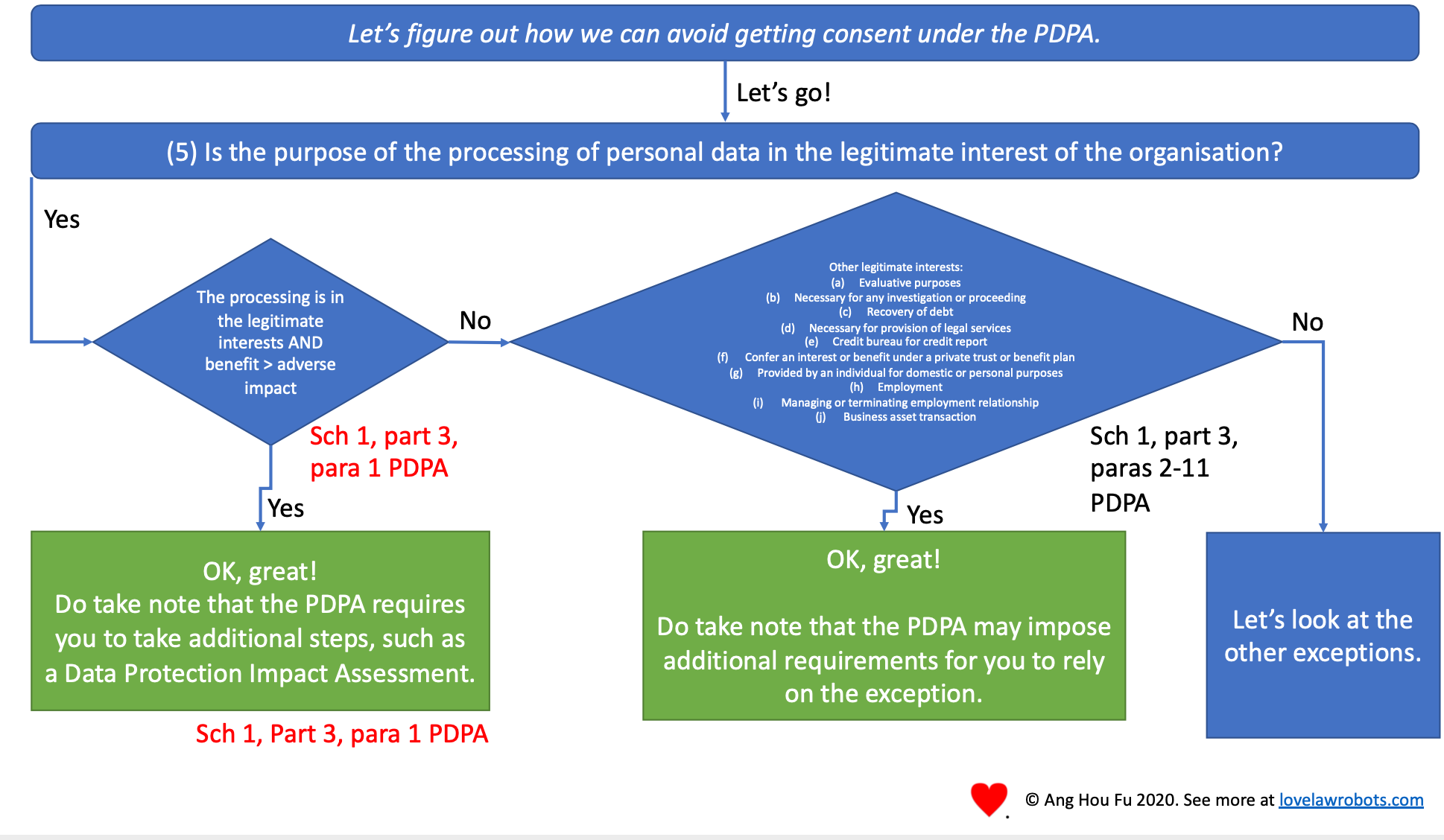

Deemed consent has expanded. A new legitimate interests exception.

A new legitimate interests exception.