Generating Legal Documents is No Longer Illegal in Germany... What about Singapore?

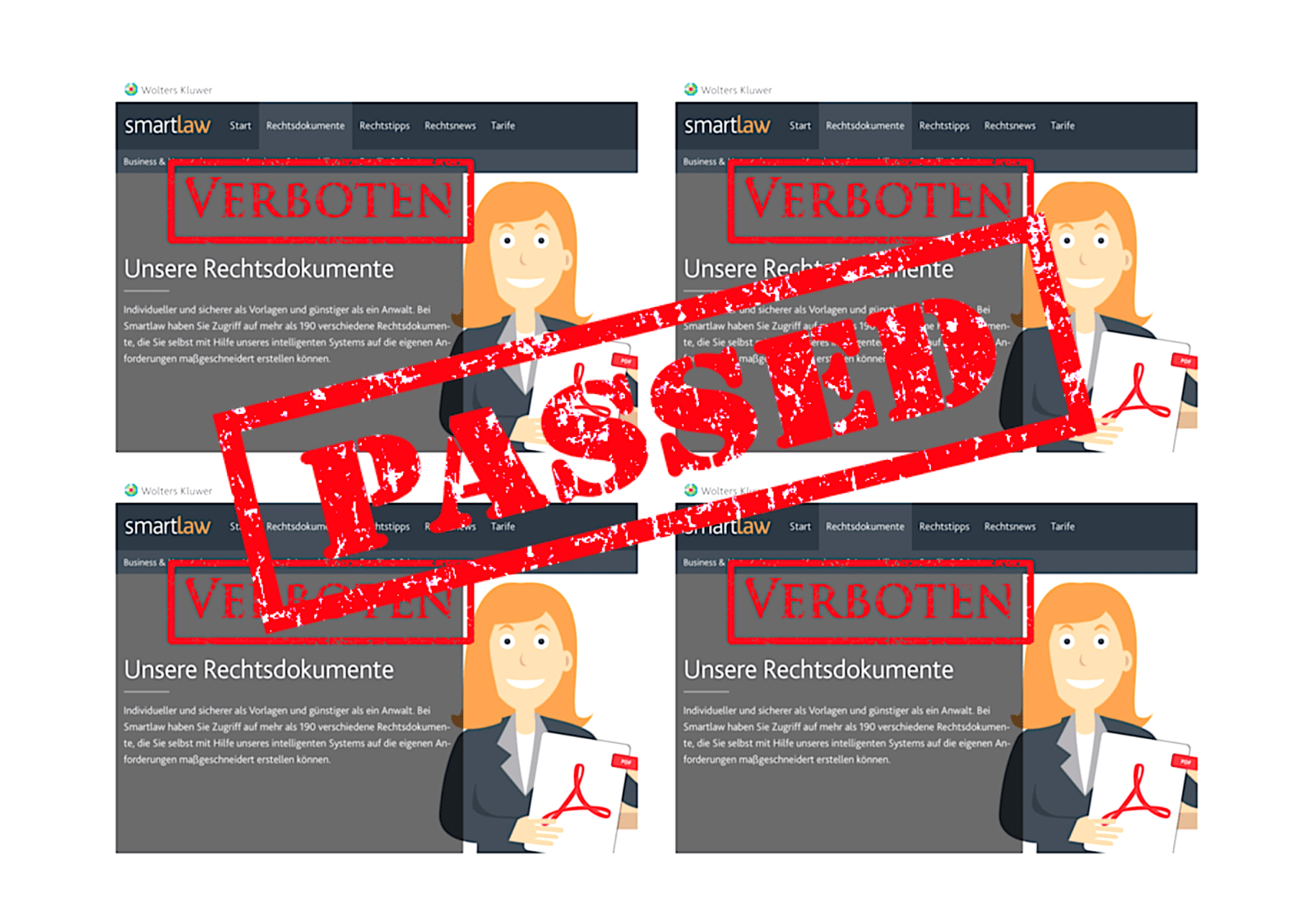

There's a conclusion on a case in Germany I have been tracking for a few years. It's one of the very few cases I am aware of where lawyers actually challenged LegalTech and if they have succeeded, killed an industry.

You can read more about the case (in English) on Artificial Lawyer. Basically, lawyers in Germany have been taking Wolter Kluwer's Smartlaw to Court for what they claim to be an unauthorised practice of law. They claimed that by providing an expert system, Smartlaw was giving legal advice, which could only be performed by lawyers (which Smartlaw wasn't). The lawyers had a victory in Cologne. However, the highest court in Germany has now confirmed that Smartlaw does not give legal advice, so the legality of Smartlaw and document generating solutions is now quite safe there.

The reasoning of the Federal Court of Justice is interesting. It held that because there was a lack of an individual assessment of the case's legal merits, Smartlaw provided no legal advice. This appears reasonable — when a programmer creates an expert system, he does not have a particular individual in mind and never knows his “client”. Besides the heavy type which usually accompanies such solutions, most consumers know that the system is not a complete replacement to seeing an actual lawyer.

What does this mean in Singapore?

Germany is pretty far in most lawyers' minds in Singapore. The differences in legal traditions suggest this decision would not have much precedential or persuasive value if a similar case were brought here.

The definitions of an unauthorised practice in Singapore are different from Germany. Based on the “I call it as I see it” approach to this issue by the courts, this could easily have gone either way.

The Importance of Being AuthorisedA recent case shows that practising law as an unauthorised person can have serious effects. What does this hold for other people who may be interested in alternative legal services?![]() Love.Law.Robots.Houfu

Love.Law.Robots.Houfu I wrote about unauthorised practices recently in response to a case in Singapore. (Free subscription required)

I wrote about unauthorised practices recently in response to a case in Singapore. (Free subscription required)

On the one hand, generating legal documents based on questions I ask a client is the hallmark of a lawyer's work, so this must be a legal practice. On the other hand, one doesn't write expert systems by imagining how to ask a real client—rules before templates before particular fact situations.

Thus, having a business proposition based on document generation, like a super-charged docassemble in Singapore, is still risky in Singapore if it clashes with lawyer regulation.

Nevertheless, the decision is still pretty relevant here.

This is one of the most vivid and realistic real-world examples of challenges to LegalTech concerning lawyer regulation. Most people imagine a robot lawyer to be a pretty advanced expert system. It's always been tempting to draw a line from “robot generating legal documents” to “legal advice” and finally “unauthorised practice”. The Germans have done it, and their highest court has answered definitively that they are not illegal. Even if there is a legally persuasive reason in our jurisprudence, it would be odd if we were an outlier.

Furthermore, while the result is satisfying, the reasoning does not give much comfort. The fine line of an “individualised assessment” might be relevant in Germany's context, but another jurisdiction like Singapore might regard the individualised assessment as necessary to protect consumers. For example, do we really want consumers to go away with printing a document that they execute wrongly? The shocking consequence of a failed will may be too much.

Who wants to do an E-Will?COVID-19 offers an opportunity to relook at one of the oldest instruments in law — wills. Is it enough to make them an electronic transaction?![]() Love.Law.Robots.Houfu

Love.Law.Robots.Houfu An earlier post considering the electronic execution of wills explains why change is prolonged here (free subscription required).

An earlier post considering the electronic execution of wills explains why change is prolonged here (free subscription required).

Honestly, I think our authorities would take the pragmatic approach. There's no denying that such expert systems explore a gap that lawyers don't or can't fulfil. An “individualised assessment” may be too expensive in several cases. Many solutions by the authorities and established parties already deploy such an approach and might be dispensing legal advice such as chatbots, wills and court forms for litigants in person. So, killing off this industry or idea at this point seems pretty far fetched.

However, this outcome might be speaking to the current limitations of an advanced expert system. Docassemble can solve many problems, but it can't do everything. On the one hand, it might take us some time to develop a highly advanced expert system, which probably has to be customised for each industry or jurisdiction. On the other hand, there are also user experience issues (clients are distraught and stressed when it comes to legal matters, and a computer asking questions doesn't seem very empathetic).

Divorce HelperDivorce Helper gives you legal information about divorce in Australia. Divorce Helper is free to use and you do not need to tell us who you are.![]() Divorce Helper

Divorce Helper![]() I find this to be a pretty good (and pretty) example of an empathetic interview.

I find this to be a pretty good (and pretty) example of an empathetic interview.

It's not impossible that a “robot lawyer” will challenge the status quo. Till then, this legal battle might still have a few more stages in it.

#LegalTech #docassemble #Law #Singapore

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow this blog on the Fediverse [Enter the blog's address in Mastodon's search accounts function]

- Contact me:

Artificial Lawyerartificiallawyer

Artificial Lawyerartificiallawyer

TechLaw.Fest 2021

TechLaw.Fest 2021

I am using my laptop to obscure the mess on my table.

I am using my laptop to obscure the mess on my table.

TODAYonline

TODAYonline

Image by

Image by  Image by

Image by  The PracticeHLS Center on the Legal Profession

The PracticeHLS Center on the Legal Profession

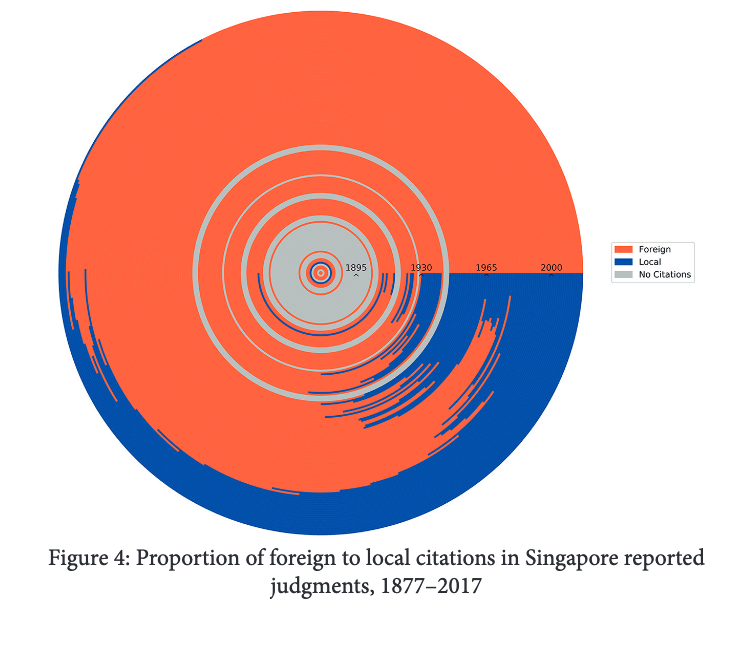

Phang Goh and Soh “THE DEVELOPMENT OF SINGAPORE LAW: A BICENTENNIAL RETROSPECTIVE” at paragraph 62/page 32. (From

Phang Goh and Soh “THE DEVELOPMENT OF SINGAPORE LAW: A BICENTENNIAL RETROSPECTIVE” at paragraph 62/page 32. (From

Legal Tech Jobs filtered for jobs with location “Singapore”. By the way, that single job does not require a computer science degree.

Legal Tech Jobs filtered for jobs with location “Singapore”. By the way, that single job does not require a computer science degree. Screenshot from

Screenshot from

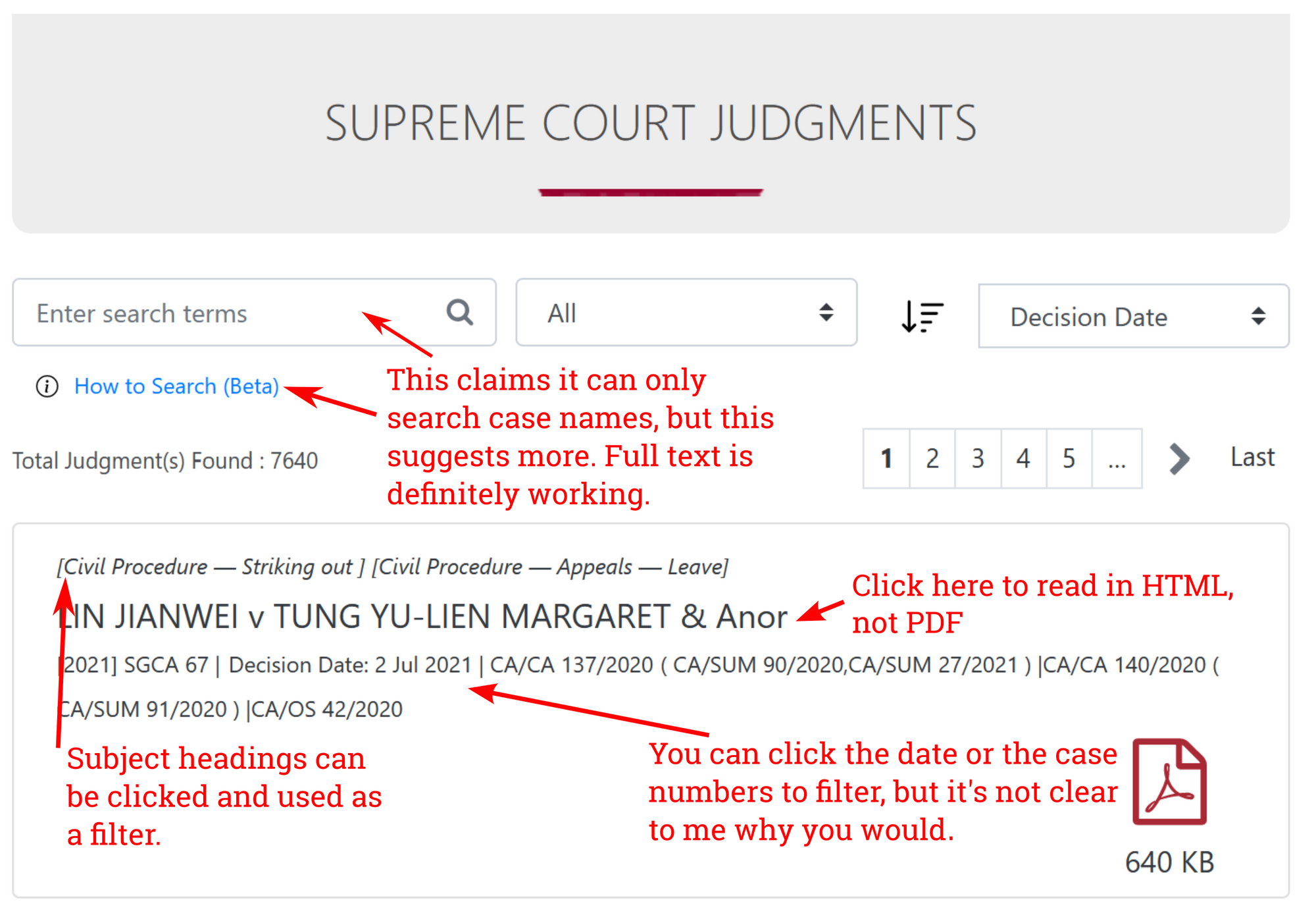

This is up to March 2020, so does not include the latest cases since then. Other notes in the

This is up to March 2020, so does not include the latest cases since then. Other notes in the