Introduction

In January 2022, the 2020 Revised Edition of over 500 Acts of Parliament (the primary legislation in Singapore) was released. It’s a herculean effort to update so many laws in one go. A significant part of that effort is to “ensure Singapore’s laws are understandable and accessible to the public” and came out of an initiative named Plain Laws Understandable by Singaporeans (or Plus).

Keeping Singapore laws accessible to all – AGC, together with the Law Revision Committee, has completed a universal revision of Singapore’s Acts of Parliament! pic.twitter.com/76TnrNCMUq

— Attorney-General's Chambers Singapore (@agcsingapore) December 21, 2021

After reviewing the list of changes they made, such as replacing “notwithstanding” with “despite”, I frankly felt underwhelmed by the changes. An earlier draft of this article was titled “PLUS is LAME”. The revolution is not forthcoming.

I was bemused by my strong reaction to a harmless effort with noble intentions. It led me to wonder how to evaluate a claim, such as whether and how much changing a bunch of words would lead to a more readable statute. Did PLUS achieve its goals of creating plain laws that Singaporeans understand?

In this article, you will be introduced to well-known readability statistics such as Flesch Reading Ease and apply them to laws in Singapore. If you like to code, you will also be treated to some Streamlit, Altair-viz and Python Kung Fu, and all the code involved can be found in my Github Repository.

GitHub – houfu/plus-explorer: A streamlit app to explore changes made by PLUSA streamlit app to explore changes made by PLUS. Contribute to houfu/plus-explorer development by creating an account on GitHub. GitHubhoufu

GitHubhoufu The code used in this project is accessible in this public repository.

The code used in this project is accessible in this public repository.

How would we evaluate the readability of legislation?

Photo by Jamie Street / Unsplash

Photo by Jamie Street / Unsplash

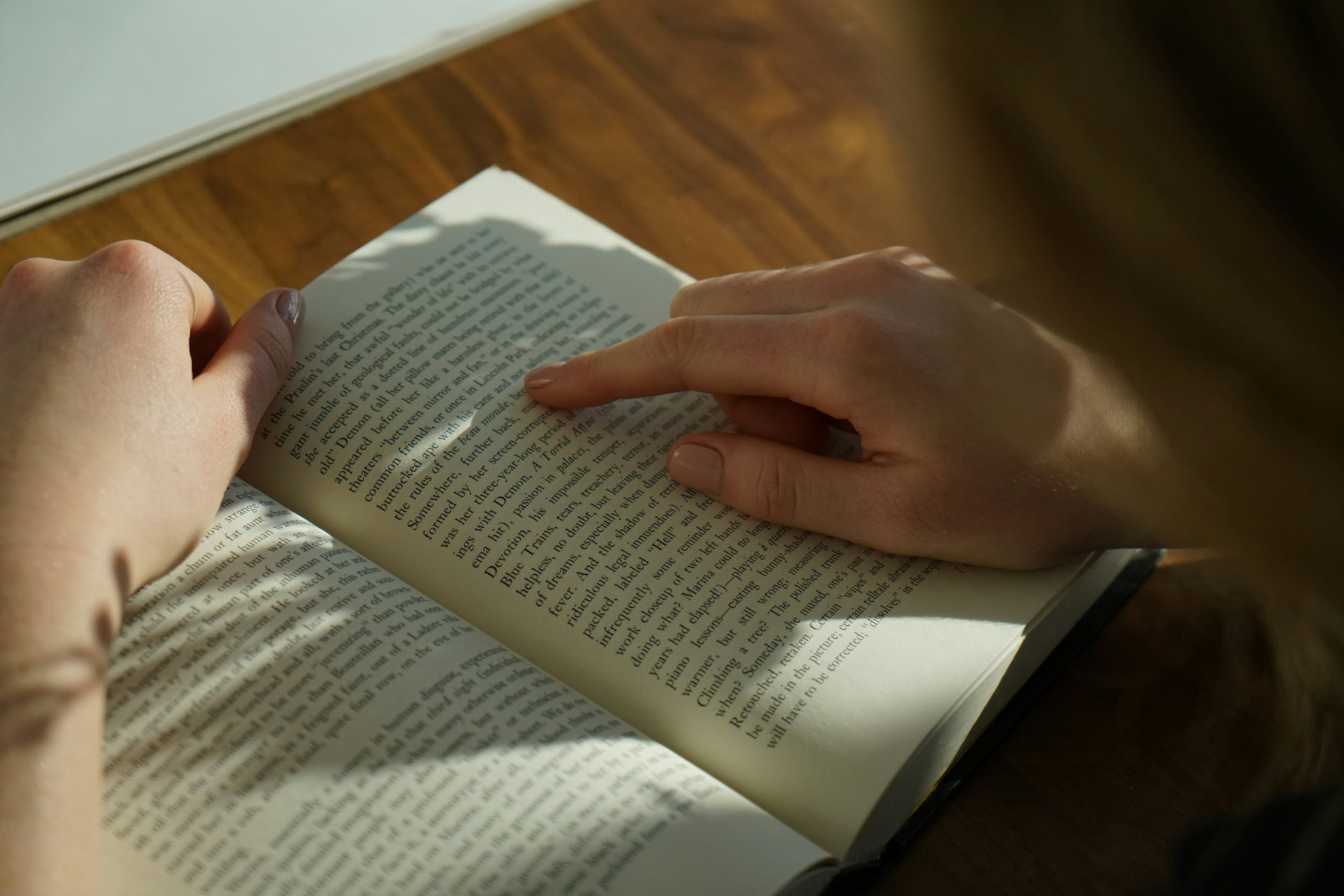

When we say a piece of legislation is “readable”, we are saying that a certain class of people will be able to understand it when they read it. It also means that a person encountering the text will be able to read it with little pain. Thus, “Plain Laws Understandable by Singaporeans” suggests that most Singaporeans, not just lawyers, should be able to understand our laws.

In this light, I am not aware of any tool in Singapore or elsewhere which evaluates or computes how “understandable” or readable laws are. Most people, especially in the common law world, seem to believe in their gut that laws are hard and out of reach for most people except for lawyers.

In the meantime, we would have to rely on readability formulas such as Flesch Reading Ease to evaluate the text. These formulas rely on semantic and syntactic features to calculate a score or index, which shows how readable a text is. Like Gunning FOG and Chall Dale, some of these formulas map their scores to US Grade levels. Very approximately, these translate to years of formal education. A US Grade 10 student would, for example, be equivalent to a Secondary four student in Singapore.

After months of mulling about, I decided to write a pair of blog posts about readability: one that's more facts oriented: (https://t.co/xbgoDFKXXt) and one that's more personal observations (https://t.co/U4ENJO5pMs)

— brycew (@wowitisbryce) February 21, 2022

I found these articles to be a good summary and valuable evaluation of how readability scores work.

These formulas were created a long time ago and for different fields. For example, Flesch Reading Ease was developed under contract to the US Navy in 1975 for educational purposes. In particular, using a readability statistic like FRE, you can tell whether a book is suitable for your kid.

I first considered using these formulas when writing interview questions for docassemble. Sometimes, some feedback can help me avoid writing rubbish when working for too long in the playground. An interview question is entirely different from a piece of legislation, but hopefully, the scores will still act as a good proxy for readability.

Selecting the Sample

Photo by Artificial Photography / Unsplash

Photo by Artificial Photography / Unsplash

To evaluate the claim, two pieces of information regarding any particular section of legislation are needed – the section before the 2020 Edition and the section in the 2020 Edition. This would allow me to compare them and compute differences in scores when various formulas are applied.

I reckon it’s possible to scrape the entire website of statues online, create a list of sections, select a random sample and then delve into their legislative history to pick out the sections I need to compare. However, since there is no API to access statutes in Singapore, it would be a humongous and risky task to parse HTML programmatically and hope it is created consistently throughout the website.

Mining PDFs to obtain better text from DecisionsAfter several attempts at wrangling with PDFs, I managed to extract more text information from complicated documents using PDFMiner.

Mining PDFs to obtain better text from DecisionsAfter several attempts at wrangling with PDFs, I managed to extract more text information from complicated documents using PDFMiner. Love.Law.Robots.Houfu

Love.Law.Robots.Houfu In one of my favourite programming posts, I extracted information from PDFs, even though the PDPC used at least three different formats to publish their decisions. Isn’t Microsoft Word fantastic?

In one of my favourite programming posts, I extracted information from PDFs, even though the PDPC used at least three different formats to publish their decisions. Isn’t Microsoft Word fantastic?

I decided on an alternative method which I shall now present with more majesty:

The author visited the subject website and surveyed various acts of Parliament. When a particular act is chosen by the author through his natural curiosity, he evaluates the list of sections presented for novelty, variety and fortuity. Upon recognising his desired section, the author collects the 2020 Edition of the section and compares it with the last version immediately preceding the 2020 Edition. All this is performed using a series of mouse clicks, track wheel scrolling, control-Cs and control-Vs, as well as visual evaluation and checking on a computer screen by the author. When the author grew tired, he called it a day.

I collected over 150 sections as a sample and calculated and compared the readability scores and some linguistic features for them. I organised them using a pandas data frame and saved them to a CSV file so you can download them yourself if you want to play with them too.

Datacsv Gzipped file containing the source data of 152 sections, their content in the 2020 Rev Edn etc data.csv.gz 76 KB download-circle

Exploring the Data with Streamlit

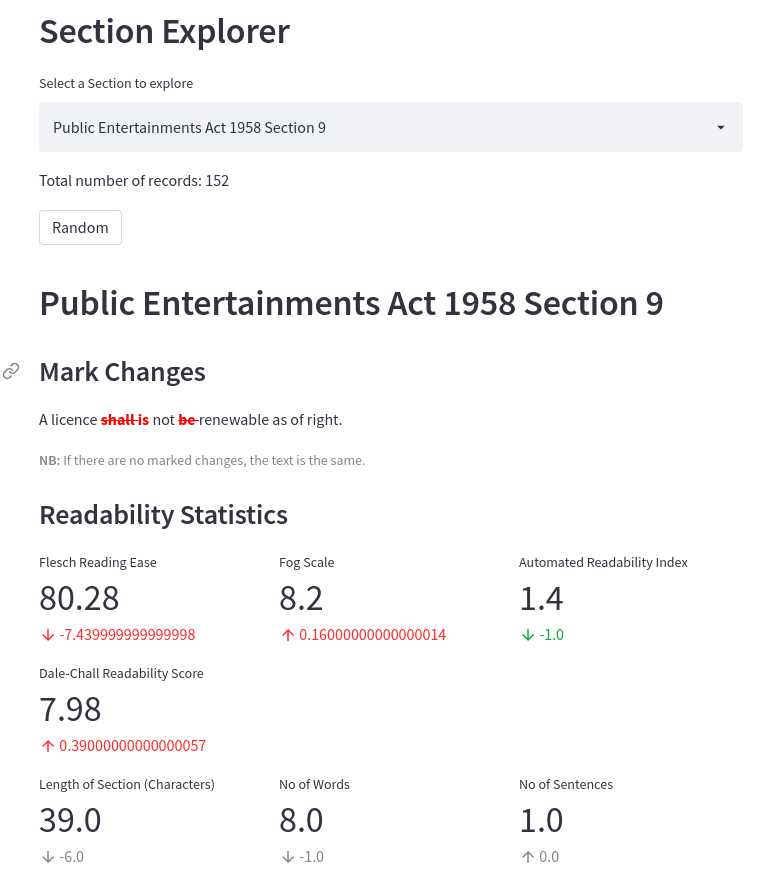

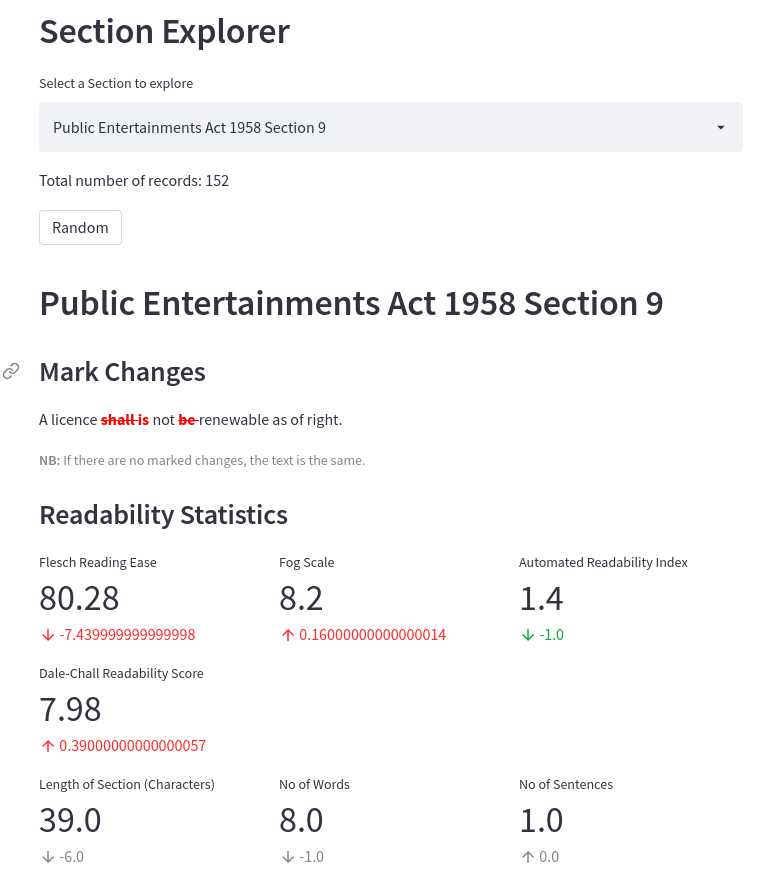

You can explore the data associated with each section yourself using my PLUS Explorer! If you don’t know which section to start with, you can always click the Random button a few times to survey the different changes made and how they affect the readability scores.

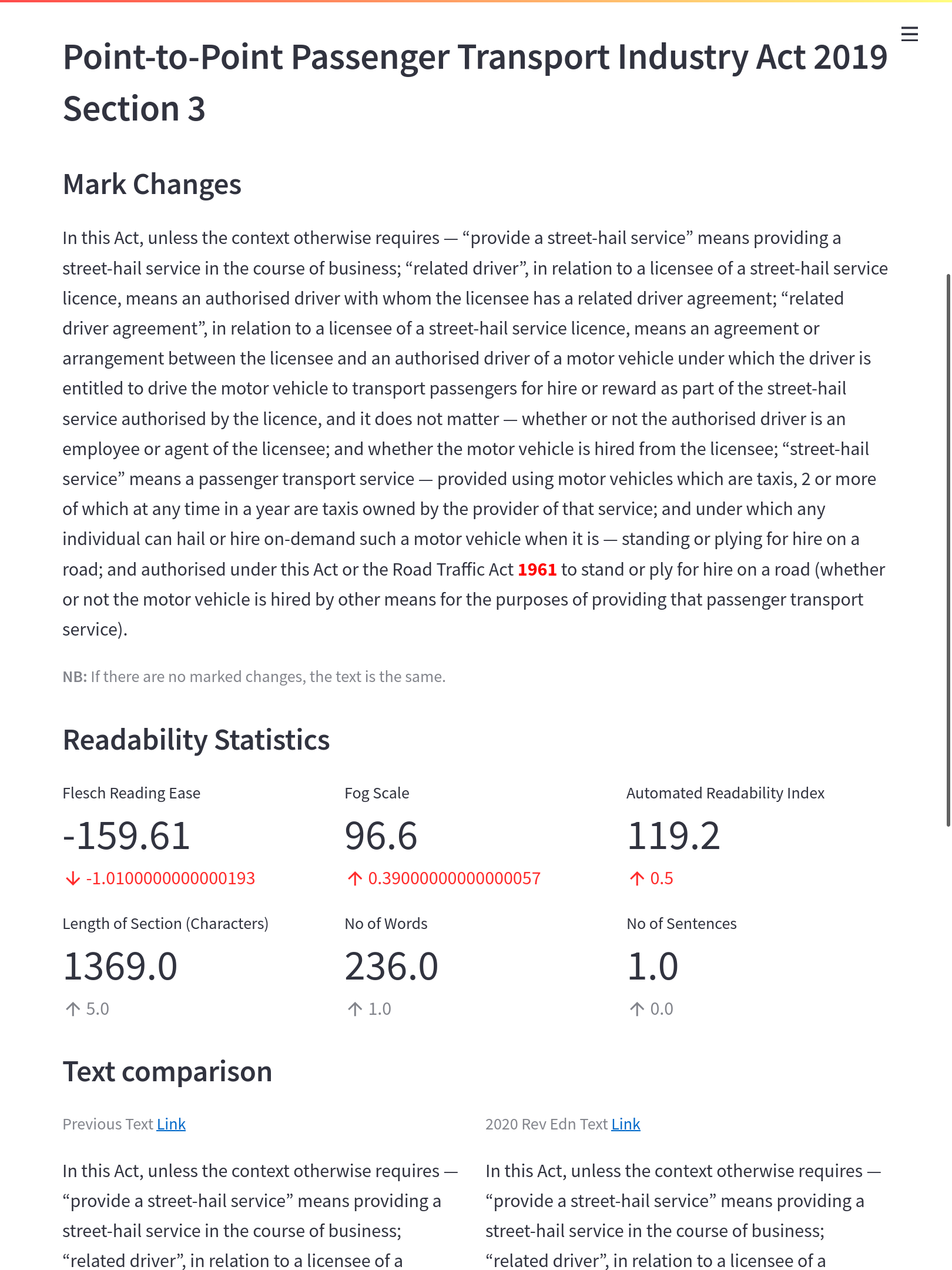

Screenshot of PLUS Section Explorer: https://share.streamlit.io/houfu/plus-explorer/main/explorer.py

Screenshot of PLUS Section Explorer: https://share.streamlit.io/houfu/plus-explorer/main/explorer.py

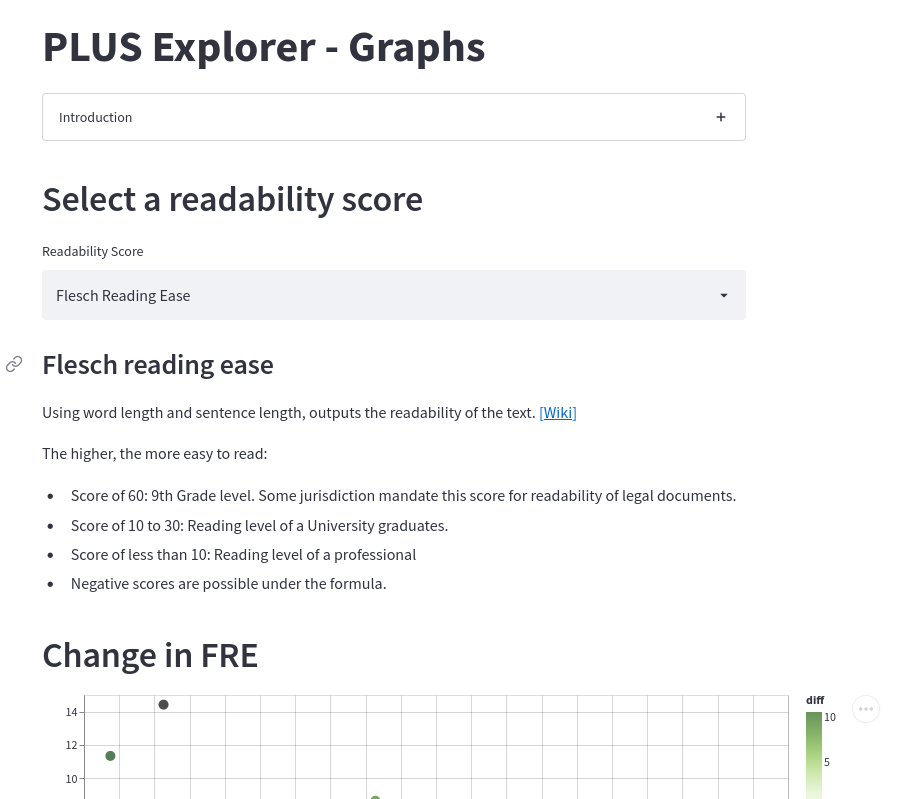

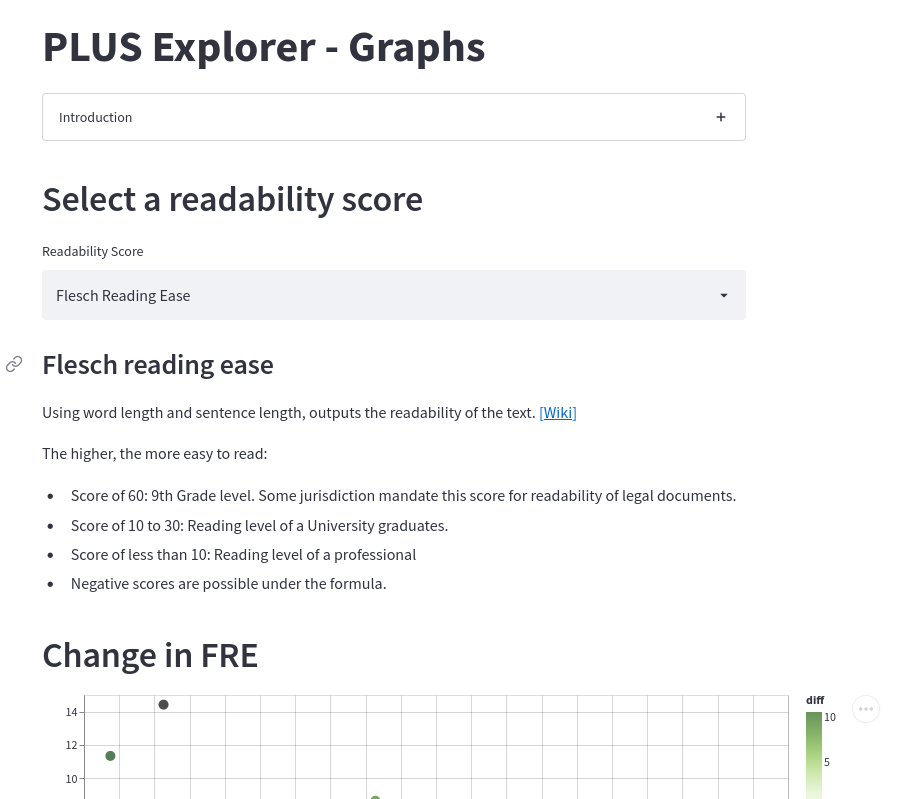

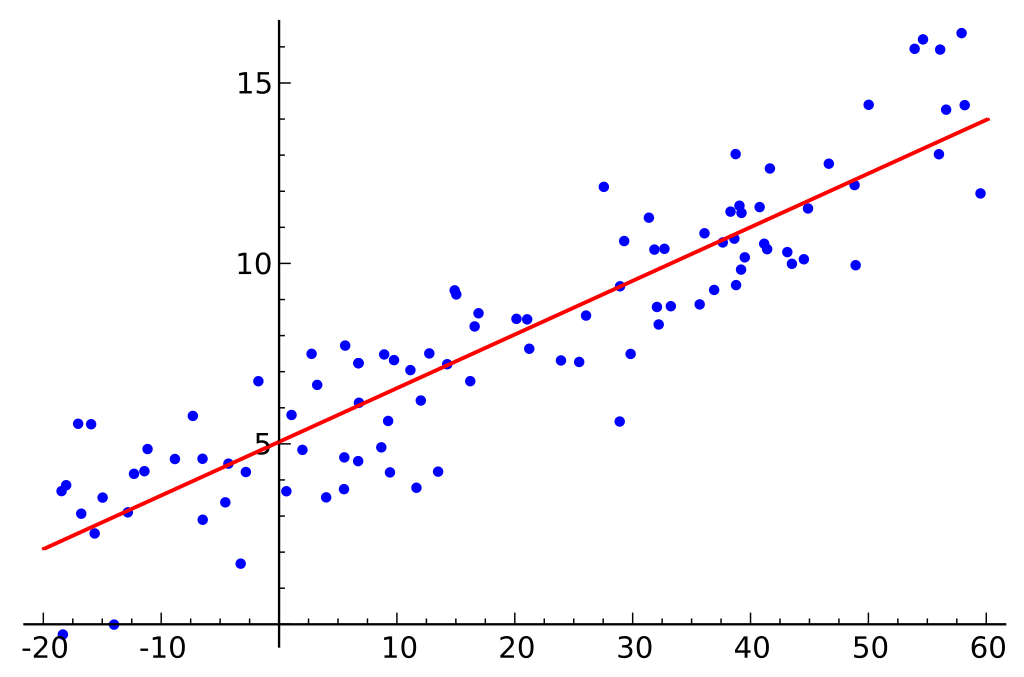

You can use my graph explorer to get a macro view of the data. For the readability scores, you will find two graphs:

- A graph that shows the distribution of the value changes amongst the sample

- A graph that shows an ordered list of the readability scores (from most readable to least readable) and the change in score (if any) that the section underwent in the 2020 Edition.

You can even click on a data point to go directly to its page on the section explorer.

Screenshot of PLUS graph explorer: https://share.streamlit.io/houfu/plus-explorer/main/graphs.py

Screenshot of PLUS graph explorer: https://share.streamlit.io/houfu/plus-explorer/main/graphs.py

This project allowed me to revisit Streamlit, and I am proud to report that it’s still easy and fun to use. I still like it more than Jupyter Notebooks. I tried using ipywidgets to create the form to input data for this project, but I found it downright ugly and not user-friendly. If my organisation forced me to use Jupyter, I might reconsider it, but I wouldn’t be using it for myself.

Streamlit — works out of the box and is pretty too. Here are some features that were new to me since I last used Streamlit probably a year ago:

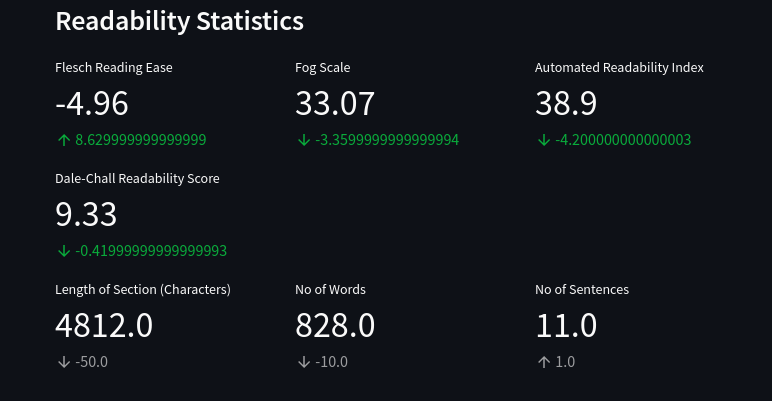

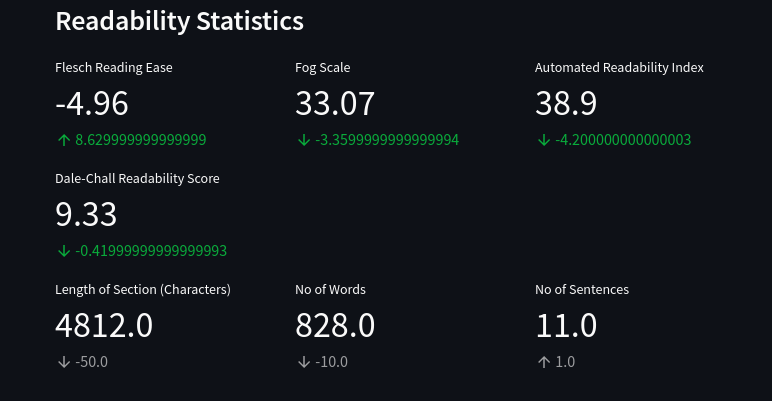

Pretty Metric Display

Metric display from Streamlit

Metric display from Streamlit

My dear friends, this is why Streamlit is awesome. You might not be able to create a complicated web app or a game using Streamlit. However, Steamlit’s creators know what is essential or useful for a data scientist and provide it with a simple function.

The code to make the wall of stats (including their changes) is pretty straightforward:

st.subheader('Readability Statistics')

# Create three columns

flesch, fog, ari = st.columns(3)

# Create each column

flesch.metric(“Flesch Reading Ease”, dataset[“currentfleschreadingease”][sectionexplorerselect],

dataset[“currentfleschreadingease”][sectionexplorer_select] -

dataset[“previousfleschreadingease”][sectionexplorerselect])

# For Fog and ARI, the lower the better, so delta colour is inverse

fog.metric(“Fog Scale”, dataset[“currentgunningfog”][sectionexplorerselect],

dataset[“currentgunningfog”][sectionexplorerselect] -

dataset[“previousgunningfog”][sectionexplorerselect], delta_color=“inverse”)

ari.metric(“Automated Readability Index”, dataset[“currentari”][sectionexplorerselect],

dataset[“currentari”][sectionexplorer_select] -

dataset[“previousari”][sectionexplorerselect], delta_color=“inverse”)

Don’t lawyers deserve their own tools?

Now Accepting Arguments

Streamlit apps are very interactive (I came close to creating a board game using Streamlit). Streamlit used to suffer from a significant limitation — except for the consumption of external data, you can’t interact with it from outside the app.

It’s at an experimental state now, but you can access arguments in its address just like an HTML encoded form. Streamlit has also made this simple, so you don’t have to bother too much about encoding your HTML correctly.

I used it to communicate between the graphs and the section explorer. Each section has its address, and the section explorer gets the name of the act from the arguments to direct the visitor to the right section.

# Get and parse HTTP request

queryparams = st.experimentalgetqueryparams()

# If the keyword is in the address, use it!

if “section” in queryparams:

sectionexplorerselect = queryparams.get(“section”)[0]

else:

sectionexplorerselect = 'Civil Law Act 1909 Section 6'

You can also set the address within the Streamlit app to reduce the complexity of your app.

# Once this callback is triggered, update the address

def onselect():

st.experimentalsetqueryparams(section=st.session_state.selectbox)

# Select box to choose section as an alternative.

# Note that the key keyword is used to specify

# the information or supplies stored in that base.

st.selectbox(“Select a Section to explore”, dataset.index,

onchange=onselect, key='selectbox')

So all you need is a properly formed address for the page, and you can link it using a URL on any webpage. Sweet!

Key Takeaways

Changes? Not so much.

From the list of changes, most of the revisions amount to swapping words for others. For word count, most sections experienced a slight increase or decrease of up to 5 words, and a significant number of sections had no change at all. The word count heatmap lays this out visually.

Unsurprisingly, this produced little to no effect on the readability of the section as computed by the formulas. For Flesch Reading Ease, a vast majority fell within a band of ten points of change, which is roughly a grade or a year of formal education. This is shown in the graph showing the distribution of changes. Many sections are centred around no change in the score, and most are bound within the band as delimited by the red horizontal rulers.

This was similar across all the readability formulas used in this survey (Automated Readability Index, Gunning FOG and Dale Chall).

On the face of it, the 2020 Revision Edition of the laws had little to no effect on the readability of the legislation, as calculated by the readability formulas.

Laws remain out of reach to most people

I was also interested in the raw readability score of each section. This would show how readable a section is.

Since the readability formulas we are considering use years of formal schooling as a gauge, we can use the same measure to locate our target audience. If we use secondary school education as the minimum level of education (In 2020, this would cover over 75% of the resident population) or US Grade 10 for simplicity, we can see which sections fall in or out of this threshold.

Most if not all of the sections in my survey are out of reach for a US Grade 10 student or a person who attained secondary school education. This, I guess, proves the gut feeling of most lawyers that our laws are not readable to the general public in Singapore, and PLUS doesn’t change this.

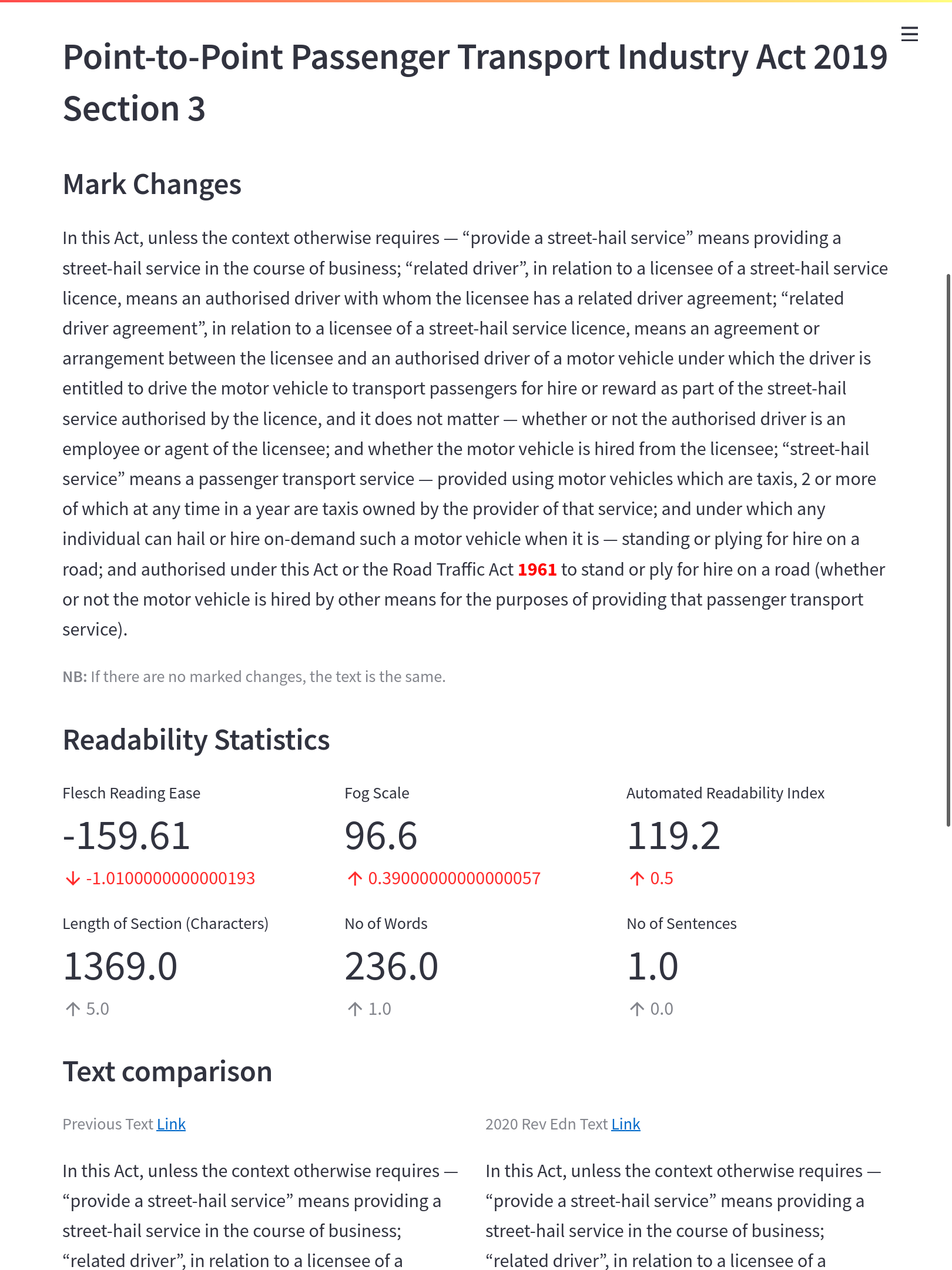

Take readability scores with a pinch of salt

Suppose you are going to use the Automated Readability Index. In that case, you will need nearly 120 years of formal education to understand an interpretation section of the Point-to-Point Passenger Transport Industry Act.

Section 3 of the Point-to-Point Passenger Transport Industry Act makes for ridiculous reading.

Section 3 of the Point-to-Point Passenger Transport Industry Act makes for ridiculous reading.

We are probably stretching the limits of a tool made for processing prose in the late 60s. It turns out that many formulas try to average the number of words per sentence — it is based on the not so absurd notion that long sentences are hard to read. Unfortunately, many sections are made up of several words in 1 interminable sentence. This skews the scores significantly and makes the mapping to particular audiences unreliable.

The fact that some scores don’t make sense when applied in the context of legislation doesn’t invalidate its point that legislation is hard to read. Whatever historical reasons legislation have for being expressed the way they are, it harms people who have to use them.

In my opinion, the scores are useful to tell whether a person with a secondary school education can understand a piece. This was after all, what the score was made for. However, I am more doubtful whether we can derive any meaning from a score of, for example, ARI 120 compared to a score of ARI 40.

Improving readability scores can be easy. Should it?

Singaporean students know that there is no point in studying hard; you have to study smart.

Having realised that the number of words per sentence features heavily in readability formulas, the easiest thing to do to improve a score is to break long sentences up into several sentences.

True enough, breaking up one long sentence into two seems to affect the score profoundly: see Section 32 of the Defence Science and Technology Agency Act 2000. The detailed mark changes section shows that when the final part of subsection three is broken off into subsection 4, the scores improved by nearly 1 grade.

It’s curious why more sections were not broken up this way in the 2020 Revised Edition.

However, breaking long sentences into several short ones doesn’t always improve reading. It’s important to note that such scores focus on linguistic features, not content or meaning. So in trying to game the score, you might be losing sight of what you are writing for in the first place.

Here’s another reason why readability scores should not be the ultimate goal. One of PLUS’s revisions is to remove gendered nouns — chairperson instead of chairman, his or her instead of his only. Trying to replace “his” with “his or her” harms readability by generally increasing the length of the sentence. See, for example, section 32 of the Weights and Measures Act 1975.

You can agree or disagree whether legislation should reflect our values such as a society that doesn't discriminate between genders. (It's interesting to note that in 2013, frequent legislation users were not enthusiastic about this change.) I wouldn't suggest though that readability scores should be prioritised over such goals.

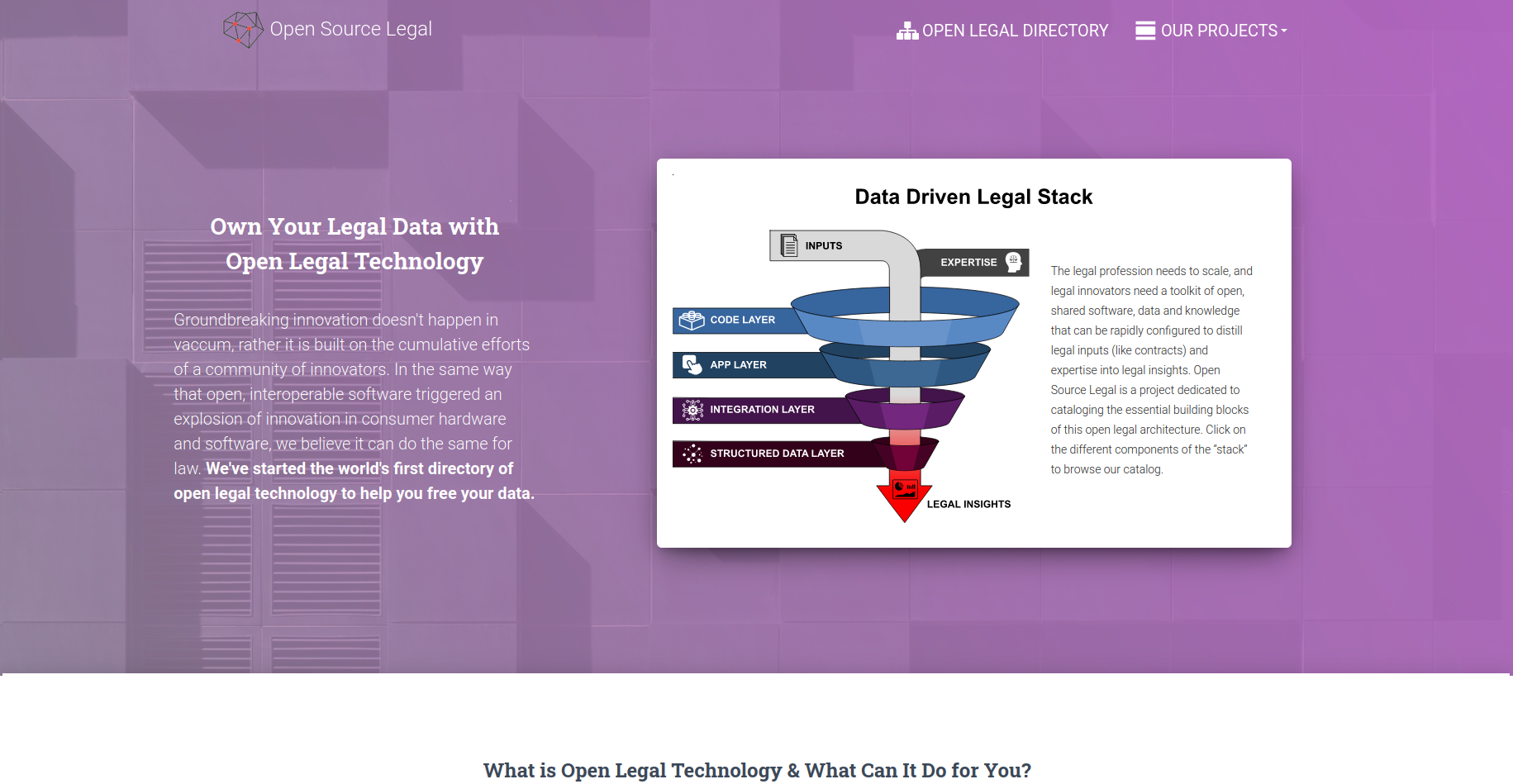

Readability scores can’t compute legal design

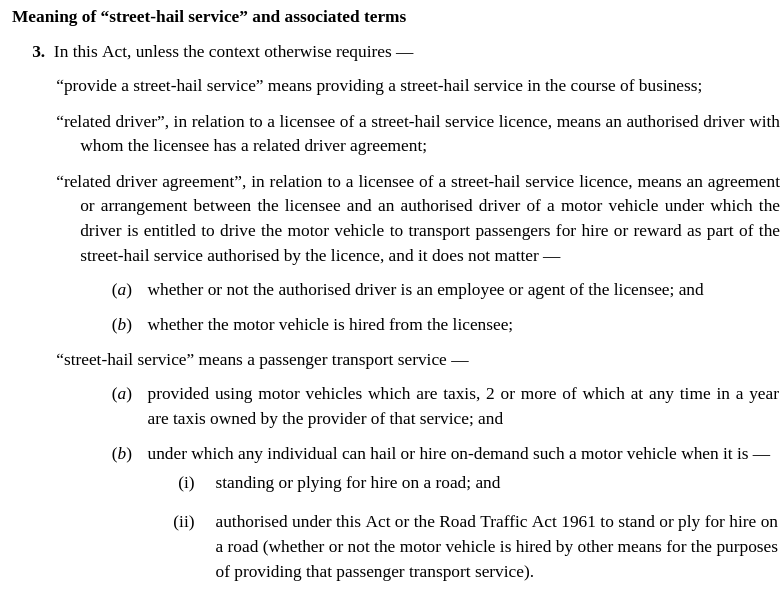

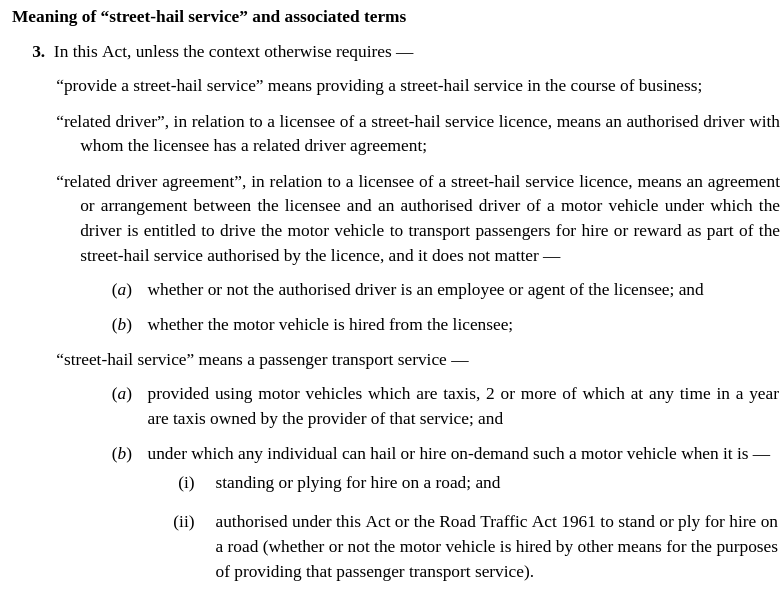

Here’s another point which shouldn’t be missed. Readability scores focus on linguistic features. They don’t consider things like the layout or even graphs or pictures.

A striking example of this is the interpretation section found in legislation. They aren’t perfect, but most legislation users are okay with them. You would use the various indents to find the term you need.

Example of an interpretation section and the use of indents to assist reading.

Example of an interpretation section and the use of indents to assist reading.

However, they are ignored because white space, including indents, are not visible to the formula. It appears to the computer like one long sentence, and readability is computed accordingly, read: terrible. This was the provision that required 120 years of formal education to read.

I am not satisfied that readability should be ignored in this context, though. Interpretation sections, despite the creative layout, remain very difficult to read. That’s because it is still text-heavy, and even when read alone, the definition is still a very long sentence.

A design that relies more on graphics and diagrams would probably use fewer words than this. Even though the scores might be meaningless in this context, they would still show up as an improvement.

Conclusion

PLUS might have a noble aim of making laws understandable to Singaporeans, but the survey of the clauses here shows that its effect is minimal. It would be great if drafters refer to readability scores in the future to get a good sense of whether the changes they are making will impact the text. Even if such scores have limitations, they still present a sound and objective proxy of the readability of the text.

I felt that the changes were too conservative this time. An opportunity to look back and revise old legislation will not return for a while (the last time such a project was undertaken was in 1985 ). Given the scarcity of opportunity, I am not convinced that we should (a) try to preserve historical nuances which very few people can appreciate, or (b) avoid superficial changes in meaning given the advances in statutory interpretation in the last few decades in Singapore.

Beyond using readability scores that focus heavily on text, it would be helpful to consider more legal design — I sincerely believe pictures and diagrams will help Singaporeans understand laws more than endlessly tweaking words and sentence structures.

This study also reveals that it might be helpful to have a readability score for legal documents. You will have to create a study group comprising people with varying education levels, test them on various texts or legislation, then create a machine model that predicts what level of difficulty a piece of legislation might be. A tool like that could probably use machine models that observe several linguistic features: see this, for example.

Finally, while this represents a lost opportunity for making laws more understandable to Singaporeans, the 2020 Revised Edition includes changes that improve the quality of life for frequent legislation users. This includes changing all the acts of parliaments to have a year rather than the historic and quaint chapter numbers and removing information that is no longer relevant today, such as provisions relating to the commencement of the legislation. As a frequent legislation user, I did look forward to these changes.

It’s just that I wouldn’t be showing them off to my mother any time soon.

#Features #DataScience #Law #Benchmarking #Government #LegalTech #NaturalLanguageProcessing #Python #Programming #Streamlit #JupyterNotebook #Visualisation #Legislation #AGC #Readability #AccesstoJustice #Singapore

Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow this blog on the Fediverse [Enter the blog's address in Mastodon's search accounts function]

- Contact me:

Love.Law.Robots.Houfu

Love.Law.Robots.Houfu

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

Metric display from Streamlit

Metric display from Streamlit

Example of an interpretation section and the use of indents to assist reading.

Example of an interpretation section and the use of indents to assist reading.

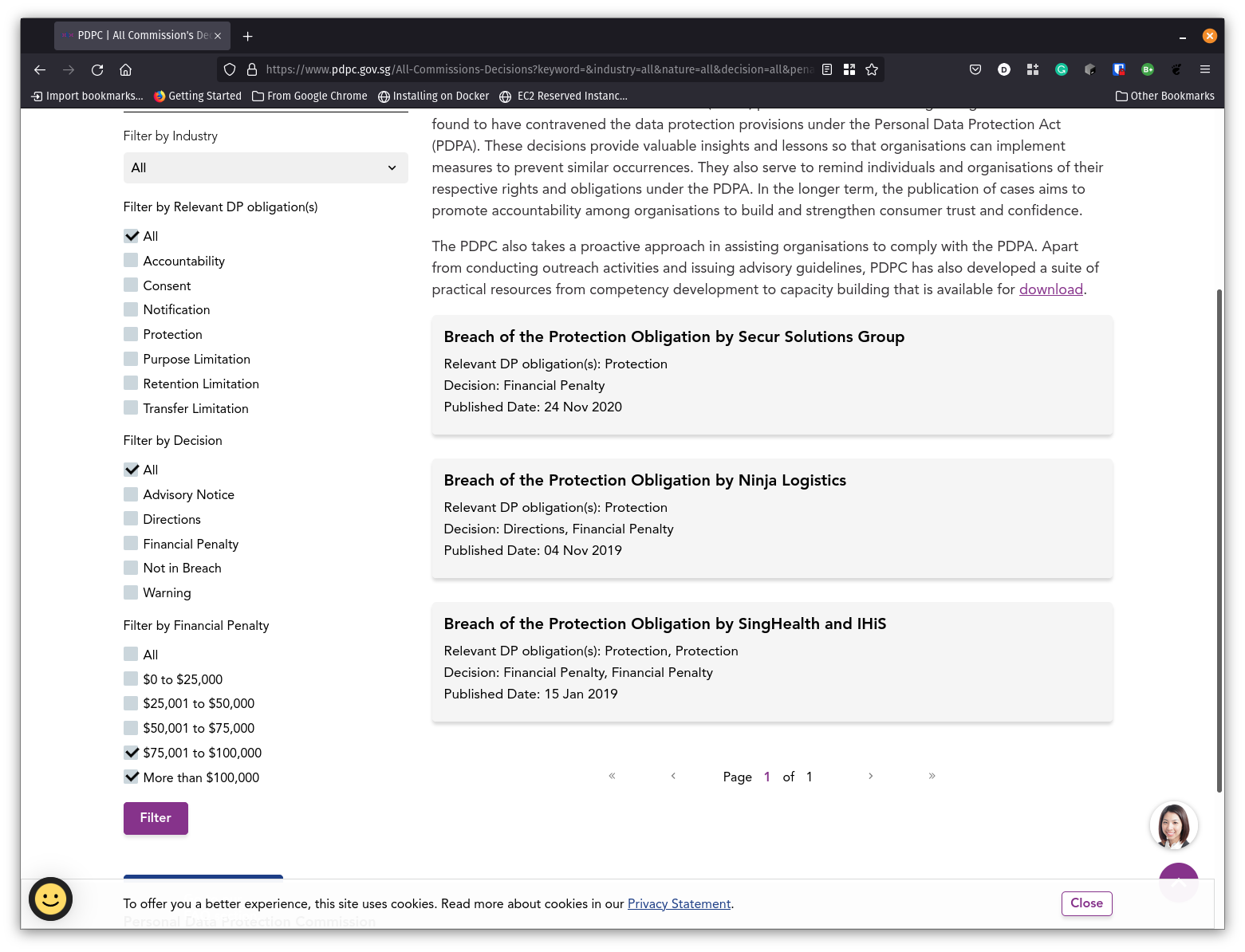

Photo by

Photo by  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:

Photo by

Photo by  The top of the financial penalty list (As of November 2021). Take note of the financial penalty filters at the bottom left corner.

The top of the financial penalty list (As of November 2021). Take note of the financial penalty filters at the bottom left corner. Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

In my ideal office, everyone gets their dustbin.

In my ideal office, everyone gets their dustbin.